| Name | SS Columbus (planned) RMS Homeric (realised) |

| Operator | Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen |

| Yard Number | 891 |

| Builder | F. Schichau, Danzig |

| Launch Date | 17th December 1913 |

| Sea Trials | 18th – 20th January 1922 |

| Maiden Voyage | 15th February 1922 |

| Tonnage | 33’526 GRT 6’900 NRT |

| Length | 236.2 meters |

| Width | 25.39 meters |

| Draught | 14.75 meters |

| Displacement | 12’300 t |

| Installed Power | 28’000 hp |

| Maximum Power | 32’000 hp |

| Propulsion | 2 triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 18 knots service (33.34 km/h) 21 knots max (38.89 km/h) |

| Crew | 750 |

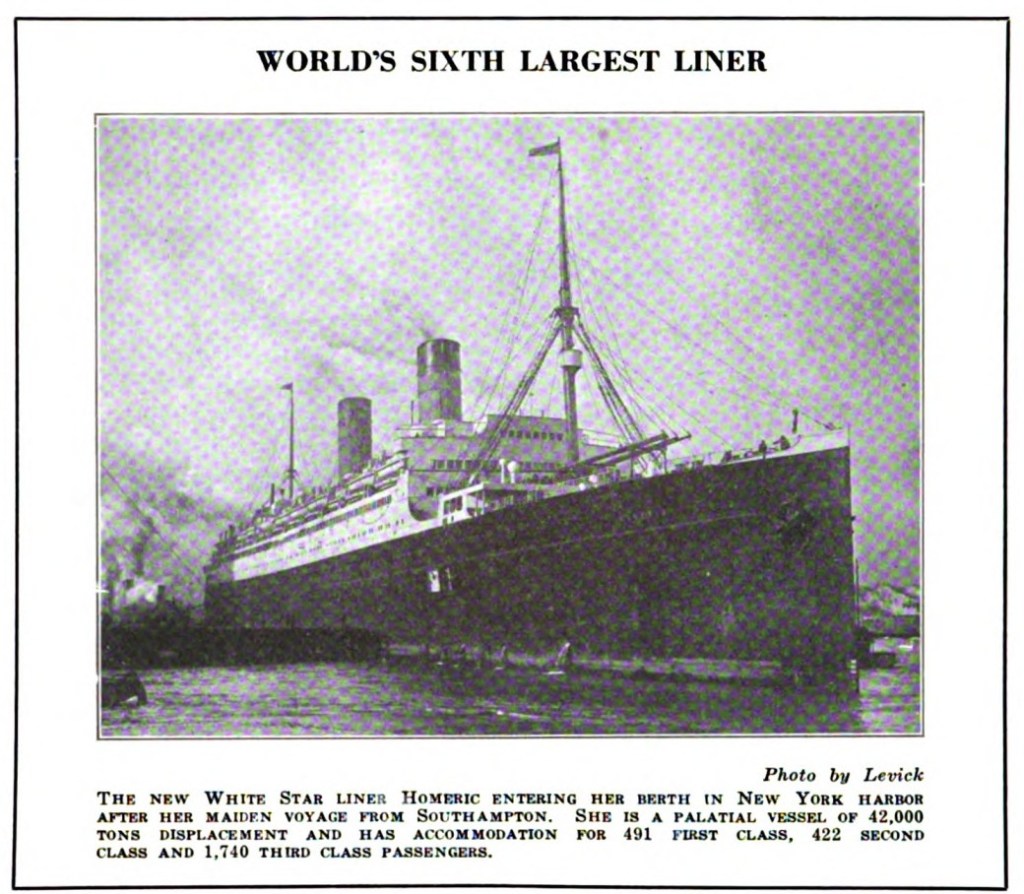

| Passengers | 1st Class: 491 2nd Class: 422 3rd Class: 1740 |

“The Ship of Splendor“: An Overview

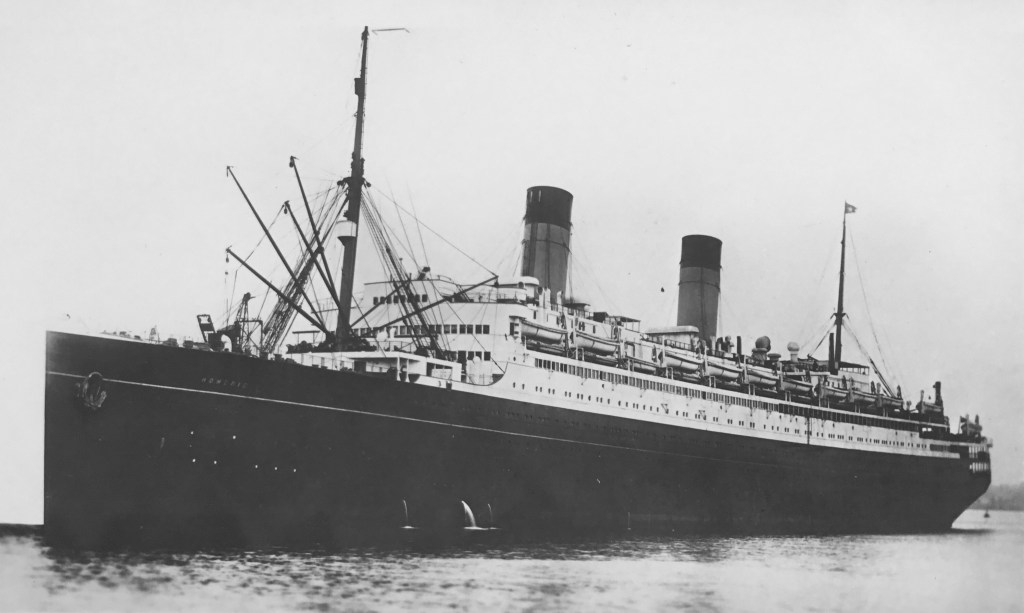

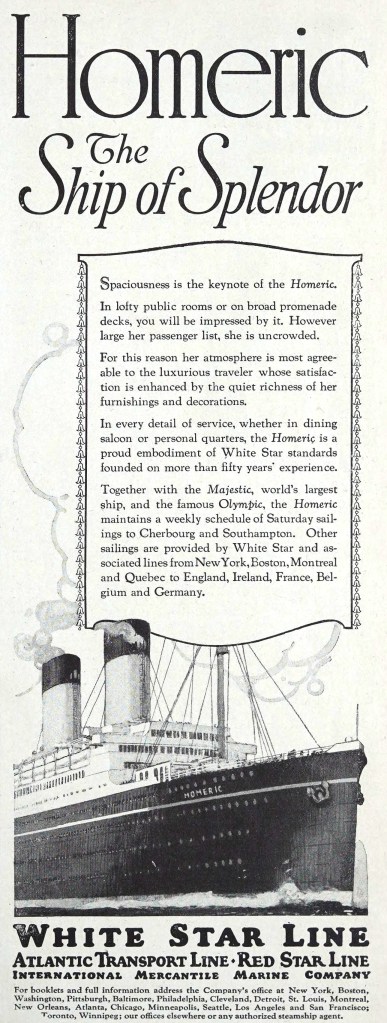

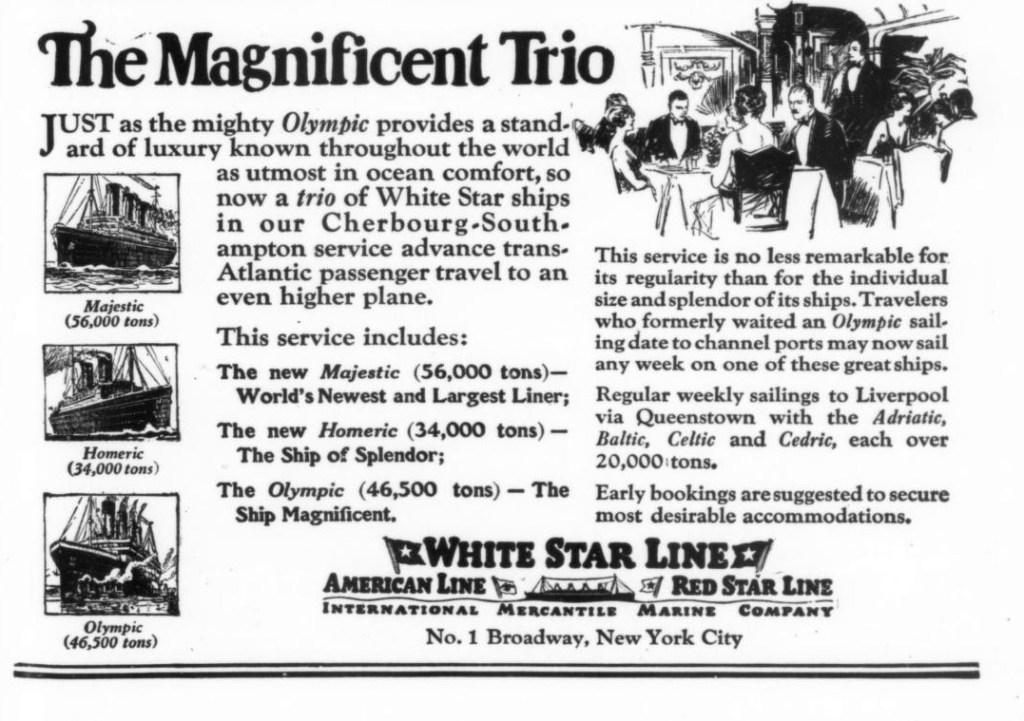

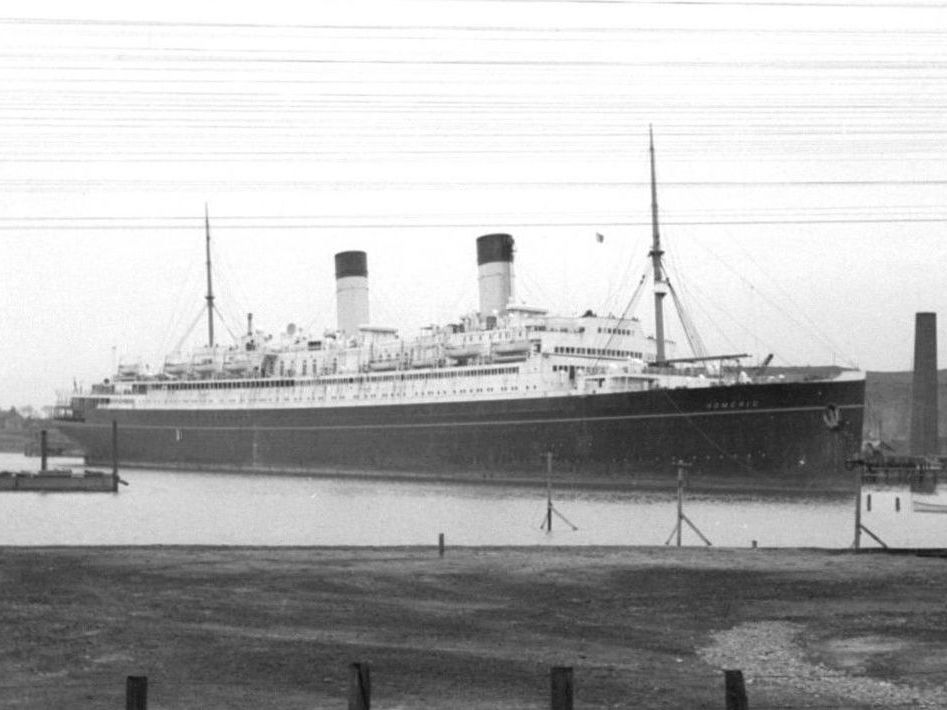

RMS Homeric and her still-German sister Columbus were two prominent liners of the 1920’s, with near-unparalleled luxury and comfort provided aboard to passengers during this time. Both these vessels were called Columbus at one point, with the vessel known as Homeric originally taking that name as the first-built of the pair, before it was passed to her sister Hindenburg as Homeric was sold to the White Star Line as a war reparation. Homeric sailed as one of “The Magnificent Trio”, arguably the most prestigious trio of ships in the world after the war years. The first was the venerable RMS Olympic, the only survivor of her class and “The Ship Magnificent” in the eyes of the travelling public. Her other running mate was fellow ex-German liner Majestic, the largest and probably most profitable liner of the 20’s.

All of this left little Homeric looking quite inadequate. At 34’000 tons compared to Olympic’s 46’500 and Majestic’s 56’000 she was never a record breaker as her mates had been, and also substantially slower not even hitting 20 knots most of the time which made her less popular than that pair, as well as other giants of the time like Leviathan, Berengaria and Aquitania. She is very largely overlooked and deemed mostly insignificant, as an unsuccessful ship that was just simply outclassed. Homeric didn’t reach the same numbers those other vessels did, but still attracted her own clientele who preferred this ship alone out of the trio for her comfort and beauty. She would never shake in the worst seas, no other ship had the same relaxed mood she did, this is “The Ship of Splendor”, RMS Homeric.

Conception

It all started with the North German Lloyd steamship company, looking to modernise and improve their fleet in the 1910’s. The 1900’s had been Lloyd’s high time as for the first seven years of the century, they were unanimously the leading line in express steamship service. Their four greyhounds, the “Kaiser Class” had absolutely swept all other vessels both in speed records and passenger numbers. But by the 1910’s Lloyd was falling behind, the Cunard Line now ran the two fastest ships in the world, sisters: Lusitania and Mauretania, and in 1911 another British firm, the White Star Line would launch the Olympic, the largest and most luxurious liner in the world. The Lloyd had plenty ships of great speed (express liners) with the Kaisers, but in terms of “intermediate” liners that focussed on size and luxury instead of speed, they had more to grow.

In 1909, the SS George Washington commenced service as the largest German liner in the world under the Lloyd flag. Compared to the 22-23 knots Lloyd’s fastest liners sailed sailed at, George Washington sailed at 19, giving her a much slower but more comfortable and economic schedule for passengers. She was a direct response to the popular “Big Four” of the White Star Line and matched their size and comfort. This ship proved to be a big success like them, and convinced Lloyd to improve this service even more with an even larger and more suitable running mate. They would be two sisters, of 35’000 GRT making them the new largest liners in the Lloyd fleet. Comfort and passenger experience would be their main driving force and not their economical service speed of 18 knots. These two new flagships would be called: Columbus and Hindenburg

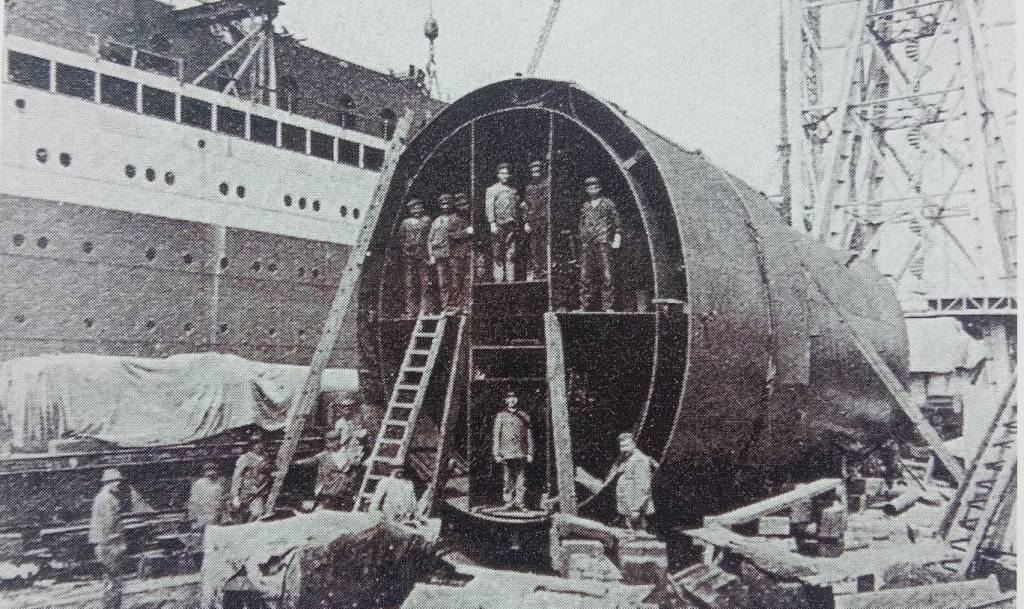

After the order was placed on the 3rd April 1912, work soon began on the Columbus at F. Schichau Shipyard, located in Danzig. The ship’s yard number would be 891. The order for her sister would be placed on the 6th September 1913 and her hull number would be 929. Columbus would be launched on the 17th December 1913. The Columbus was designed by famed architect Paul Ludwig Troost, who would later go on to design the record-breaking superliner Europa. He was also in charge of the interior spaces of the Columbus, and made them spacious and bright for maximum comfort at sea. For instance, the First Class Dining Saloon was designed to be 850m³, even bigger than the one onboard the Olympic which had been the previous holder of the title. Another interesting detail was that Kaiser Wilhelm II himself ordered a $7000 Imperial Suite to be used by himself, whenever he would voyage in the future. A rumor was that Wilhelm also planned to take a victory cruise aboard this liner upon Germany’s apparent victory in the First World War.

Construction and Design

Technical Specifications of the Columbus

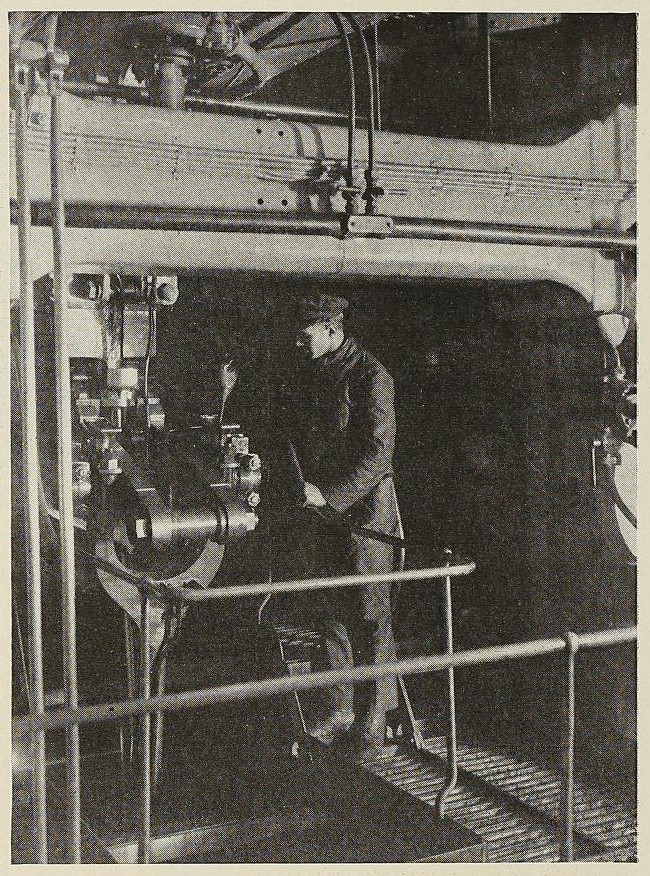

The ship was built with double screws, making her the largest liner of that configuration in the world and they would be driven by two 4-cylinder triple expansion steam engines. The cylinders were 50.5, 86.5, and 96.5 inches in diameter and had a stroke of 70 inches. Each engine produced 16’000 horsepower for the ships total speed of 18 knots. These engines were serviced by two boiler rooms with one uptake each for the two funnels. They would operate 12 double-ended coal-fed boilers that worked at 210 psi. The ship had a classic straight-stem bow as of the time, as well as a fashionable counter stern which had 35-ton rudder. For cargo, the ship had six hatchways operated with derricks on her two masts and samson posts. The ship was well-designed with 14 water-tight bulkheads and 12 compartments. Following newer regulation standards the liner was fitted with lifeboats for all passengers and crew aboard. As was typical for the time, the ship would be built with emigrant-carrying in mind with room for 1750 third class passengers, and 529 first and 487 second class.

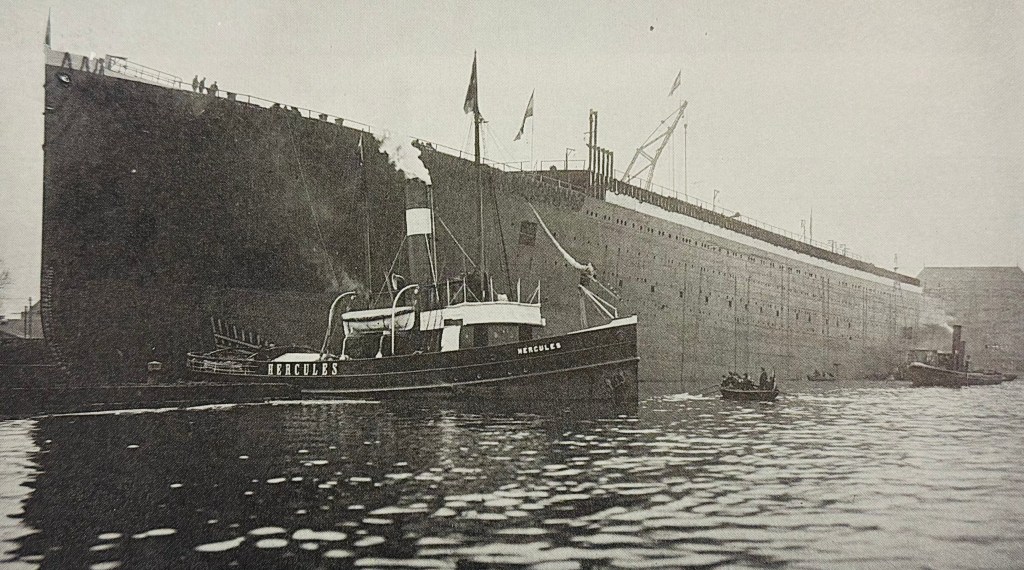

The Launch

Once the 15’000-ton steel hull was complete, it was time for the launch. This took place on the 17th December 1913. Tensions were high within the Lloyd for this ship to enter service as a year earlier in May, their most longstanding-rival, Hamburg Amerika Line had launched the 50’000 tonner Imperator .This HAPAG liner was the largest in the world by far with sisters on the way, and the Lloyd liner was second on this day. As was a classic tradition, the ship was launched by the monarchy. Not one, but both Kronprinz Wilhelm and Kronprinzessin Cecilie, heirs to the throne would both be present today. In addition to them were many thousands that had gathered by the slipway since 10:30 to watch the largest liner in the Lloyd fleet be launched.

Cecilie would christen the ship, and send the colossal structure into the water 12:00 sharp for the first time today, destined to carry the torch of the North German Lloyd further.

The First World War

Work continued on Columbus throughout early 1914. By June 19th, NDL was confident that their ship would be completed in 4 months for her maiden voyage on October the 3rd. This was to be a nine-day trip and was supposed to coincide with the 422nd anniversary of Christopher Columbus discovering America with the Columbus landing in New York on October 12th. This was never to be.

On June 28th 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated and the world was never the same again. Germany entered war against Russia on August 1st 1914, and materials and work towards completing Columbus stopped during this month. At this point the ship was moved to Danzig to be finished after the war, she was 90% complete now. Her sister Hindenburg was nowhere near complete, only being a double bottom still on her slipway at F. Schichau. The only things needing finishing before setting sail was some furnishing of the interiors and general finishing off before she would be ready for her maiden voyage. But that voyage under the Lloyd never took place as Germany signed the Armistice on the 11th November 1918, ending “The Great War”. Almost a year later on June 28th 1919, the Treaty of Versailles was signed which was much despised by the Germans. One article that changed German merchant shipping forever was Part VIII, Article 244, Annex III:

“The German Government, on behalf of themselves and so as to bind all other persons interested, cede to the Allied and Associated Governments the property in all the German merchant ships which are of 1,600 tons gross and upwards; in one-half, reckoned in tonnage, of the ships which are between 1,000 tons and 1,600 tons gross; in one-quarter, reckoned in tonnage, of the steam trawlers; and in one-quarter, reckoned in tonnage, of the other fishing boats.“

With a single line, all vessels of only 1600 GRT or more of the gargantuan merchant marine fleet of Germany, -including the largest shipping line in the world Hamburg Amerika Line, had to be ceded over to the Allies as war reparations. In terms of tonnage, Germany’s fleet was now only 1/10th of what it had been prior to the war and the Columbus was gone with it. She was a particularly enticing prize as one of the largest German vessels since Britain had lost many important vessels before and during the war. With that she was handed over to the British government in 1920. What was likely the most premier pre-war British shipping company – the White Star Line, was currently in desperate need to restore their three-ship weekly service of titans. The lead ship: Olympic was the only one left standing after the war, as she lost one sister before the war and one other during it.

White Star had initially ordered a 40’000 ton ship immediately after the war from Harland and Wolff under the name of Homeric to replenish their lost tonnage. They needed large ships in a hurry, and quickly cancelled that contract and instead bought the nearly-complete Columbus from the Reparations Commission on June 24th 1921 to be the second of their trio. The final gap was filled in by another incomplete German ship: the Bismarck which was to be the largest ship in the world. White Star initially considered naming the Columbus as Oceanic after their famed liner of 1899 that had been lost in the war, as well as their very first ship built back in 1870. They wound up choosing Homeric as they did not want to give that prestigious name to a ship built in a foreign country. A team from Harland and Wolff was sent to supervise the final completion in Hamburg up to White Star standard. As compensation for taking the Columbus, the NDL was allowed to keep five small ships equalling 39’505 GRT being: the Yorck, Seydlitz, Göttingen, Gotha, Westfalen and Holstein. According to the Chairman of the White Star Line: Harold A. Sanderson, the ship had been acquired by negotiation rather than compulsion and the German authorities had handed her over with every courtesy. The ship was interestingly completed under her original name of Columbus for White Star, with that name and in NDL colours.

Did the Columbus attempt her sea trials before the war began?

An extremely interesting article from the New York Times recalls an event published on the day the Homeric arrived at Southampton on the 20th January 1922 after completing her sea trials. It details that in late July 1914, this ship was capable of starting her sea trials before the war had began, whilst still under German ownership as: Columbus. The ship lay in Danzig, ready for a trial run with the North German Lloyd having invited many esteemed guests to sail too. They were right about to depart: cargo had been loaded, guests were aboard, and people had said their goodbyes when the captain received a telegram. After 30 worried minutes for the guests onboard, the ship finally turned around and docked, disembarking its passengers and cargo, and the boilers were dampened. It was the eve of The Great War, and the ship then lay in silence, bounded by ropes to the pier until finally a few weeks before her sea trials under the White Star Line.

By January 20th, the Homeric was finally ready, -8.5 years after she had been intended to sail on her maiden voyage. The ship had been unusually completed ahead of schedule by her Danzig shipbuilders and thus her maiden voyage would commence a week earlier. On February 15th, 1922 the Homeric sailed on her maiden voyage after “very satisfactory” sea trials under much fanfare. During her trials she reportedly developed an excellent top speed of 21 knots. It had been nine years since the ship had started construction, and would now finally enter service.

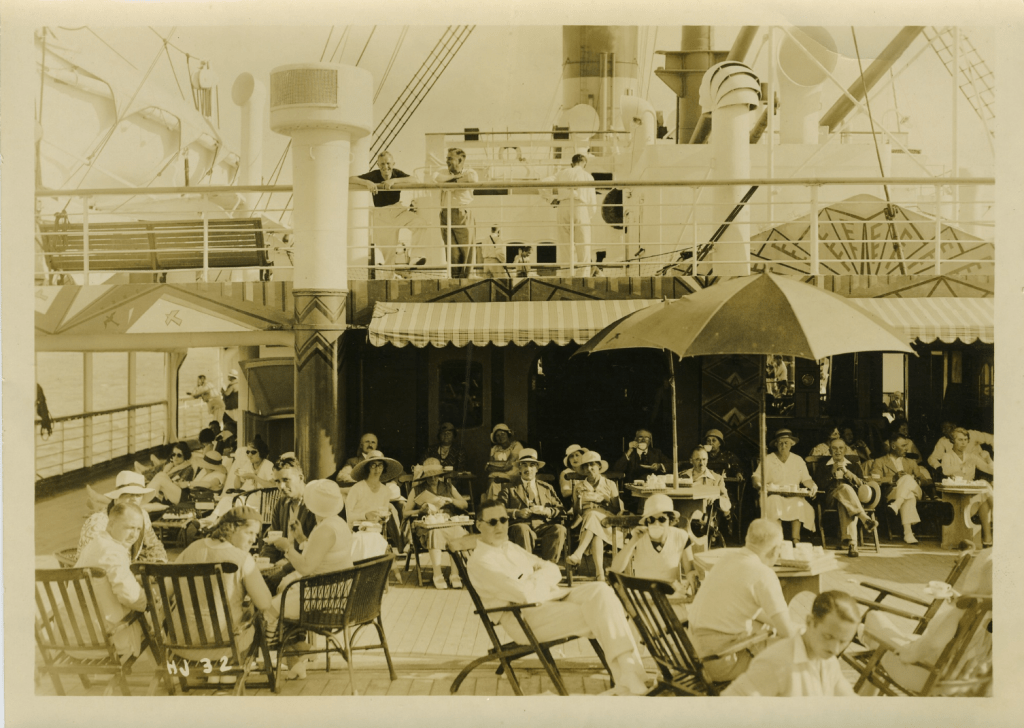

Onboard Facilities of the new Homeric

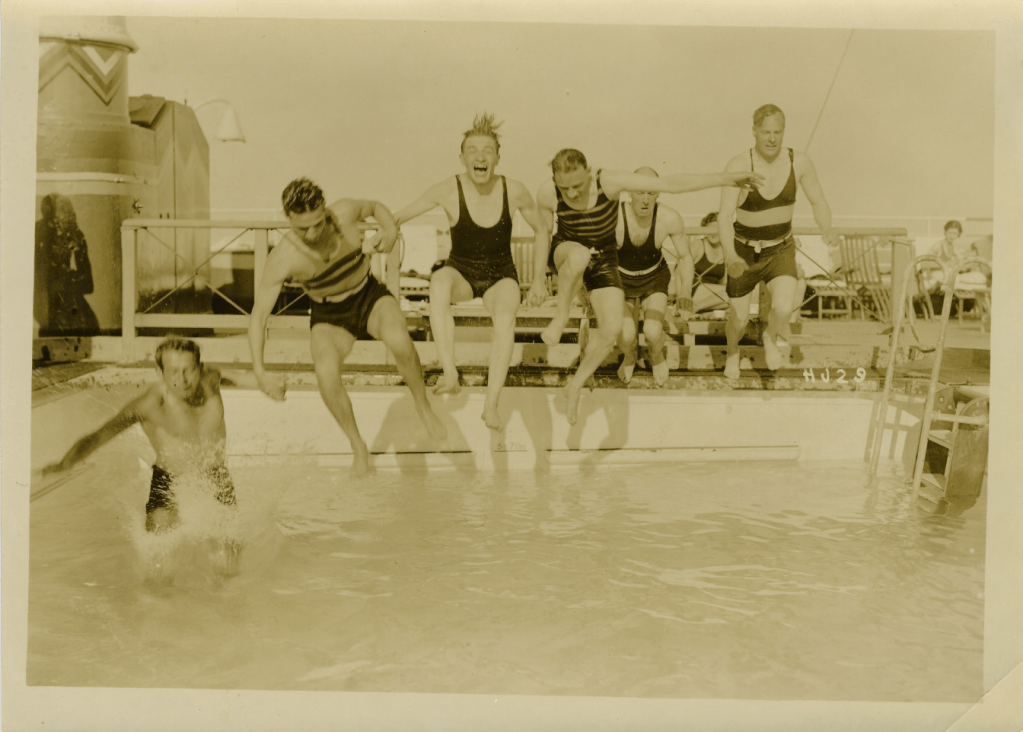

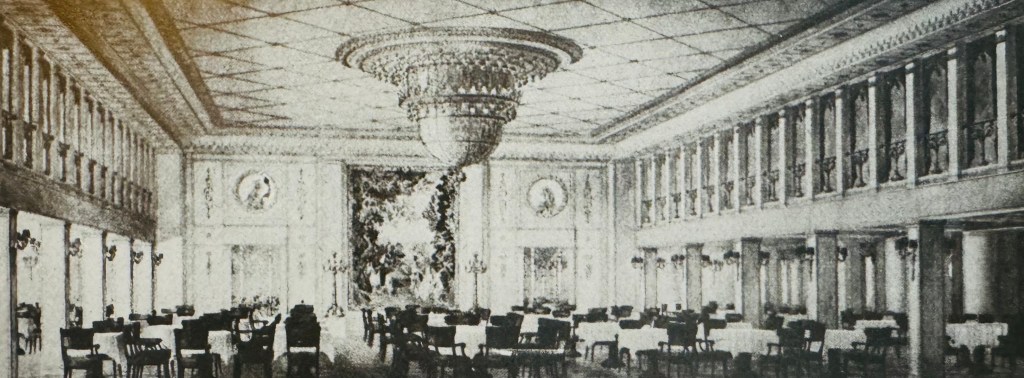

When finally completed for the White Star Line, Homeric was very well equipped for her duties when service would commence with her maiden voyage in 1922. Her greatest asset was her furnishings and inside decoration as the liner was marketed as being: “fitted up exactly like a modern hotel”. This meant she had windows instead of portholes in areas, staterooms with proper beds instead of berths, and each First Class stateroom had its own private bath and telephone line.

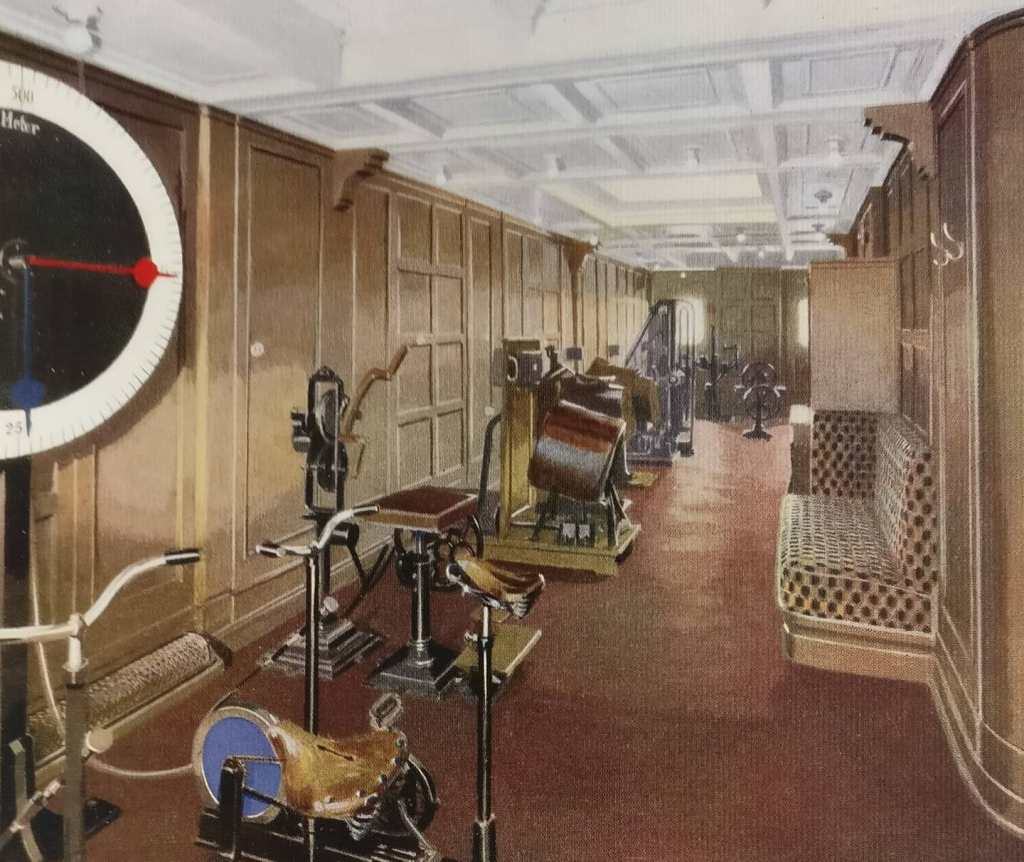

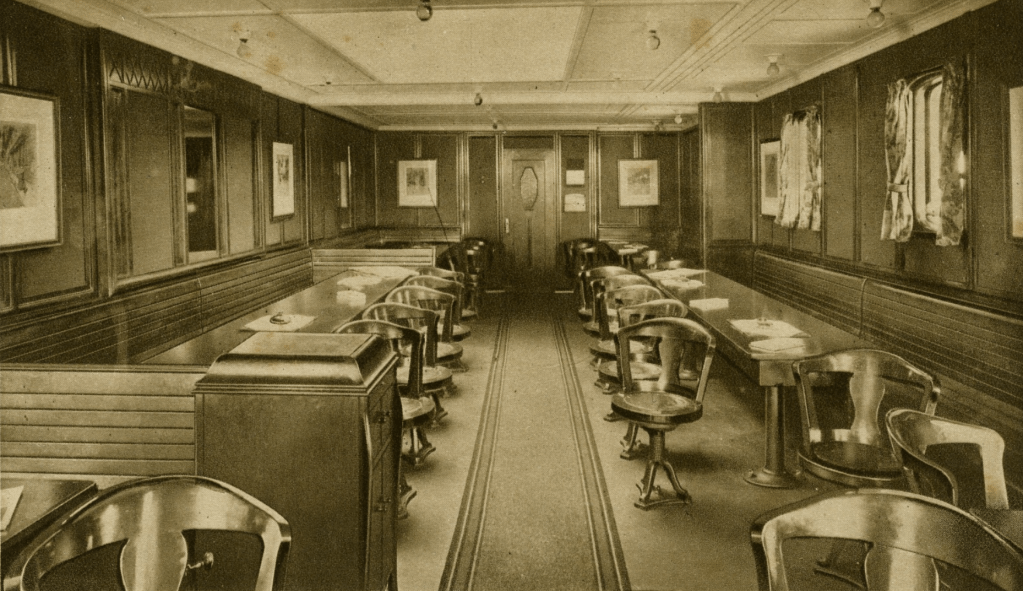

She would have two passenger elevators that would service decks A, B, C, D & E. All cabins on B-E decks would have running hot and cold water. For passengers wishing to develop photographs they would take during the voyage, she had an on-board dark room for them to be developed in. There would also be an on-board stenographer to type up messages passengers would like to send. The ship’s other amenities included a state-of-the-art gym, children’s playroom, various shops, hairdressers, calls to be made by radio, two electric-light baths on C-Deck, a dance-floor that could arranged in the lounge and of course an on-board doctor and even a Nurse just for the lady passengers, to help those in need. The rooms themselves were truly spectacular, like Majestic her public rooms would be larger and have much higher ceilings than their contemporaries on board the Olympic, most notably the Lounge, Dining Saloon and Smoking Room.

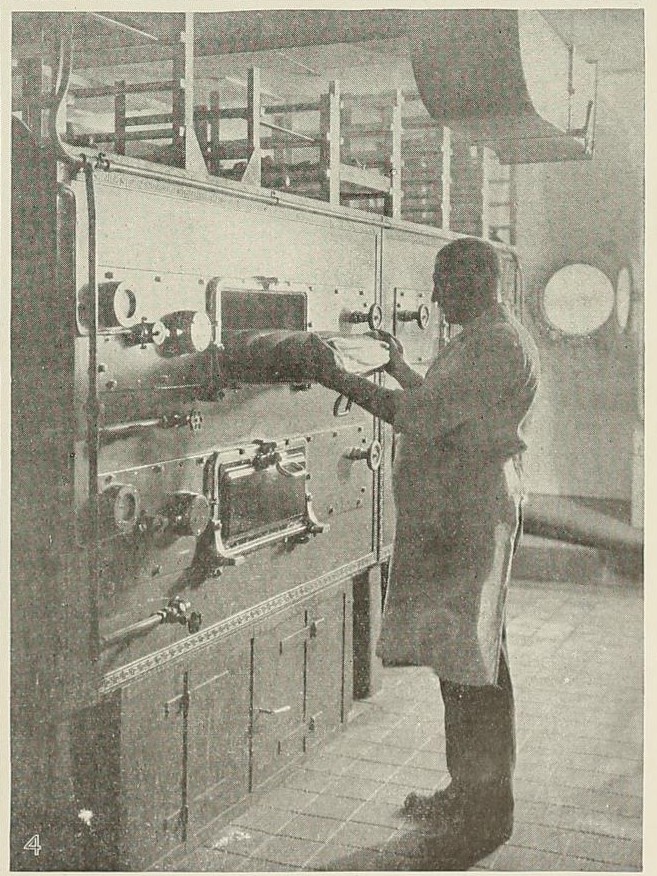

The ships bakery was a facility that was given much praise and attention. Homeric carried a team of 20 bakers to satisfy the needs of her guests. This team could satisfy the needs of a town of 5000 people every day, with the use of their kitchen. Homeric’s bakery was a big step forward as bakeries aboard other liners tended to be small, cramped, dimly-lit and ventilated. Homeric’s bakery consisted of two rooms on the starboard side of the ship, with windows open to the sea. As the general rule was 1 pound of bread per person per day, the 20 bakers of the Homeric could easily satisfy the needs of the roughly 3200 people aboard the ship during rush season easily, and with a large margin to spare.

As for onboard music, the Homeric carried a skilled group of musicians as all White Star ships. They played 2 times a day at evening, and once during Sunday evenings always in the First Class Lounge. There was even a Jazz Trio who would play four times a day, in between the segments done by the orchestra.

Deck Plans and layout of the Homeric

The ship was built to utilize her top two decks of superstructure purely for comfort. All of her main public rooms were located on these two decks, except for her main dining saloon which was located on B Deck.

Bridge Deck would house the Gymnasium as well as most of the outdoor deck space.

Boat Deck was fully surrounded by a long First Class Promenade which encircled her best rooms. Starting from the fore, was the Drawing Room + Reading and Writing Room, two long corridors containing shops and staterooms, The First Class Lounge & Grand Staircase, The Card Room, and then finally The First Class Smoking Room and the Verandah Cafe that led outdoors.

Promenade Deck contained the second First Class Promenade, entirely enclosed by glass with deckchairs compared to the upper one. This deck housed entirely First Class Cabins, both First Class Entrances, the former connecting to the Grand Staircase and two pantries.

A Deck consisted mostly of cabins too, but also had the Enquiry Office, Purser’s Office and Telephone Room. This deck housed the largest and grandest cabins on the ship, her private suites, and almost every cabin was equipped with private baths.

B Deck housed the largest and grandest room on the ship by far and one of the largest at sea: The First Class Dining Saloon. Guests could prepare themselves right before they entered as this room was joined by a Barber’s Shop on the port, and a Ladies Hair Dressing Room starboard.

A tour through the interior spaces of the RMS Homeric : “The Ship of Splendor”

“Surely the de luxe hotel at sea idea has been realized by the Homeric. Appropriate to her name she is a tremendous epic.”

-White Star Line advert

[i]

[i]

First Crossing

Maiden Voyage:

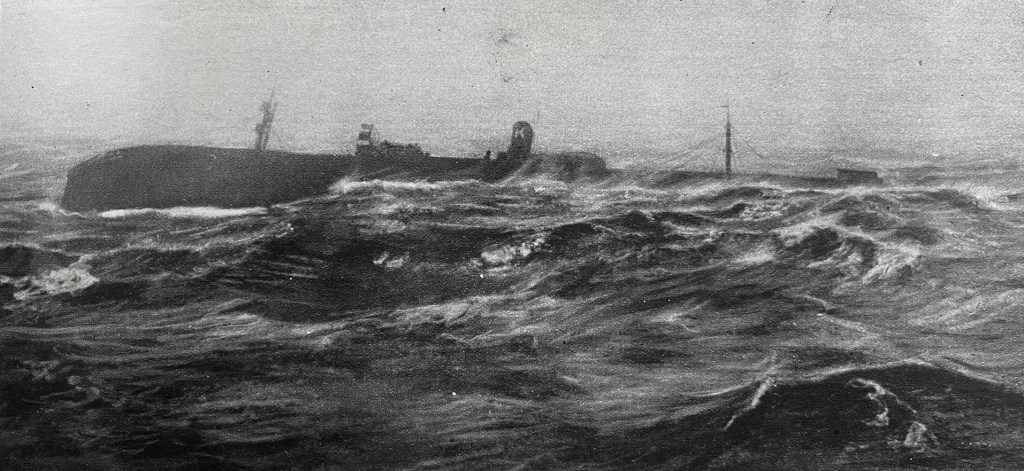

The ship had her maiden voyage on the 15th February 1922 under the command of Captain FB Howarth. Things started out slightly less-promising than usual when Homeric was caught in rough weather, which delayed her arrival in New York for two days. She arrived on the 24th February instead of the 22nd with a crossing time of 7 days, 23 hours and 23 minutes at a speed of 15.75 knots, but still made a big impact. After docking in New York, 600 steamship agents visited her and were so astounded at this palace: they described her as having “The handsomest dining saloon and public rooms ever seen on a ship in this port”. The next day on the 25th, 1600 further guests were invited to tour the ship. Several American shipbuilders present also stated that the hand-carved ceilings of the Homeric were: “the finest specimens of the cabinetmaker’s art ever seen”. Even though the Homeric wasn’t theirs anymore, she was still heralded by German journals as: “A masterpiece of German shipbuilding”. The guests then enjoyed a fine lunch in the Lounge and had a dance orchestrated by the band afterwards. Homeric was the largest twin screw vessel in the world, and sixth largest overall. White Star Line had spared no expense with this ship, after purchasing her they spent an additional $800’000 to make her just as pleasant as Olympic and Majestic.

Return Maiden Voyage:

At noon on the 1st March 1922, Homeric began her return maiden voyage with very high spirits. After what had happened on the way forwards, Captain Howarth said there was great interest among the crew to return her back home in good time. A very special guest had been aboard the Homeric for both crossings of her maiden voyage: Philip E. Curry with his wife and daughter, who was the director of the International Mercantile Marine Company which owned the White Star Line. He had been impressed by Homeric’s performance and stability during the way there, and spoke of the new liner highly. He wasn’t the only official present: P. A. S. Franklin who was the president of the company, stood on the pier and watched the big liner depart as the nearby steamers blasted their whistles in a salute.

Voyage Times:

The next few voyages of the Homeric would show improvements. Her second voyage from Cherbourg to New York on February 30th would see a much better performance of 6 days, 20 hours and 47 minutes with an average speed of 18.32 knots. The passengers who landed “expressed delight with the ship”.

Homeric under the White Star banner

Settling into service, Homeric very quickly found her niche among other ocean giants for her pure comfort and stability. Due to her machinery installation, the ship was incredibly steady even in rough seas, easy to maneuver, had zero vibration and was very fuel efficient. Passengers were quick to praise the ship for being uncrowded and even stated: “Few vessels of any line ride more smoothly than the Homeric”. This combination made the voyage itself an extension of the destination, and attracted many passengers making her popular. The ship sailed proudly in conjunction with Olympic from New York to Southampton, and was soon joined by the Majestic, which had her maiden voyage in May of the same year, creating White Star Line’s “Magnificent Trio”

Operating Homeric was the polar opposite of operating the new Columbus of the North German Lloyd, her old sister the ex-Hindenburg who had received her sisters name and entered service in 1924. Columbus had horrible vibration issues despite both ships having the same engine layout, which annoyed passengers. In fact during one voyage in 1927, Columbus snapped a propellor shaft and her engines raced, before literally tearing themselves apart mid-voyage. They were temporarily replaced with similar engines from a freighter, but finally NDL replaced them with steam-geared turbines – drastically increasing her speed to a maximum of 24 knots. Homeric never got an upgrade like this and sadly her speed soon became a detriment to White Star’s three-ship service.

Now that all three vessels were in service, Majestic and Olympic quickly settled in the absolute tops of passenger-carrying lists, with Homeric multiple spots behind them. During 10.5 years from February 1922 – June 1932, the performances of the “Magnificent Trio” was as follows:

Majestic: 312 crossings, 156 round trips: 337’888 passengers carried. (Average of 1083 per crossing)

Olympic: 320 crossings, 160 round trips: 241’340 passengers carried. (Average of 754 per crossing)

Homeric: 232 crossings, 116 round trips: 129’186 passengers carried. (Average of 557 per crossing)

White Star had a very specific timetable in mind, when operating their three flagships. Originally all three Olympic-Class ships were intended to sail as follows: One ship would leave Southampton for New York on Wednesday each week. The second would leave New York on Saturday back to Europe. The third would be transiting the Atlantic at this moment in any direction. With this timetable, and each ship sailing at 21-22 knots, their trio would provide a weekly service of six-day crossings, the most competitive on the market. The surviving Olympic-Class ship: Olympic, unsurprisingly did this perfectly. Majestic did an even better job with her faster speed, passenger capacity and greater luxury. During her first season on the Atlantic, Homeric’s best crossing speed was 18.69 knots, whilst Olympic’s was 22.55 and Majestic’s was 24.02 knots.

One will quickly realize Homeric’s average 18 knots was a detriment, as she took approximately 7 days to cross the Atlantic – hindering White Star’s timetable. They quickly tried to speed her up, converting her to burn oil alongside other tweaks during her winter overhaul in 1923, but the ship still wasn’t satisfactory at 19.5 knots. Truly her triple-expansion engines and two propellor-combination was not capable for express service.

The Raifuku Maru Disaster

Many liners took part in amazing rescues at sea during their lifetime. Homeric would sadly not follow suit and was unable to help avert a tragedy. On the 19th April 1925, Homeric was on a usual Atlantic crossing when she received a distress signal from the Raifuku Maru. She was a Japanese cargo vessel that left had left Boston on the 18th April, with a full cargo of wheat bound for Hamburg. She had a GRT of 5857 and a length of 117m (385 feet). The ship was led by Captain Izeki, with wireless-operator Masao Hiwatari. Only a day after leaving Boston, the Raifuku Maru got trapped in the worst storm seen that month, a force 9 gale. As the ship started to leak, Hiwatari began to send out several distress mesages to other ships in the vicinity:

“Maru in danger like dagger. Hurry quick.”

“Ship meeting heavy weather and held starboard twenty eight degrees. Smashed lifeboats into board and In danger.”

“Ship 39 degress low, please, quick, assistance”

“Now very danger come quick”

The Homeric responded:

“Coming as fast as possible, twenty knots. Now seventy miles from you. Can you take to your lifeboats? Maintain wireless for bearings.”

Homeric was 60 miles away and was was captained by Captain John Roberts of the White Star Line. He immediately turned the ship in a straight line towards the Raifuku Maru, speeding at an astonishing 20 knots to make it there in time. Things on board were extremely tense as the seas rattled the big ship, the stokers hurled coal into the boilers, and all eyes were on the horizon scanning ahead. Finally they arrived after 5 hours at 10:55am and Homeric heard the last transmissions:

“No wind anger, but coming; lifeboat from sixty miles here.”

“We are waiting for lifeboats”

Homeric then herself broadcasted her last message to the Raifuku Maru:

“Homeric alongside, but crew not yet picked up.”

Raifuku Maru was in precarious situation, her cargo of wheat had come loose and thrown the ship off balance in the rough seas at around 5am. What’s worse is that water had caused it to swell and burst, and now the ship was unable to pitch back onto an even keel as she continued to get slammed by waves. These waves destroyed the lifeboats, and the ship was listing hard at 30 degrees. Homeric was steered within 150 yards of Raifuku Maru and lifeboats were prepared to be launched. Unfortunately no opportunity to help arose as the seas were too rough and the tiny amount of oil aboard did nothing to quieten it. Only minutes later at 11:18am, the Raifuku Maru went down, taking all hands with her. The Cunarder RMS Tuscania arrived just as the Raifuku Maru sank and was unable to assist either. Homeric stayed nearby until 12:03am, trying to find survivors. Passenger testimonials conflicted heavily on whether survivors were sighted in the water, or clinging to the Raifuku Maru, or if they were floating debris. After this sad sight, one last message was broadcasted from the Homeric:

“OBSERVED STEAMER RAIFUKU MARU SINK IN LAT 4143N LONG 6139W REGRET UNABLE TO SAVE ANY LIVES”

When news reached the mainland, there was massive outcry. The Japanese press called racism at Homeric’s inability to save lives, and American papers had said “No heroic effort was made to save lives“. The Japanese seamen’s union in Kobe appealed to the international community, and the emperor issued 300 yen payments to their grieving relatives. The actions of Captain Roberts caused debate as some passengers of the Homeric had been certain they had seen survivors struggling in the water who were left unaided. A further 123 passengers were certain there were no survivors and signed a testimonial praising Captain Roberts for his actions during the disaster. Other Captains who had also heard Raifuku Maru’s distress calls and were in the same storm had said: “It would have been suicide for the Homeric’s master to launch the lifeboats.”

The prior racism point was uncalled for however, as Captain Roberts had helped save 1200 people from another wreck in the past when he was Chief Officer. He personally knew that it was just not possible to lower lifeboats in seas that rough and risk more lives. Truly Homeric was unluckily placed in a very bad position, causing an unhappy and tragic mark on her career.

Those Lost of the Raifuku Maru:

| Commander-Captain H. Izeki. | Chief Officer-Capt. H. Fujiwara. | First Officer-M. Mori. | Second Officer-S. Miki. | Third Officer-S. Nishihara. |

| Chief Engineer-S. Nakamura. | First Engineer-M. Hirano. | Assistant Engineer -M. Onishi | Assistant Engineer -M. Ono | Wireless Operator-M. Hiwatari. |

| Boatswain-C. Tanaka. | Carpenter-T. Umino. | Quartermaster -M. Unebasami | Quartermaster -G. Yasuda | Quartermaster I. Umeda, |

| Quartermaster T. Shirakata. | Sailor -S. Fujitani | Sailor –I. Nakamura. | No. 1 Oiler-T. Mukae. | No. 2 Oiler-S. Kitahara. |

| No. 3 Oiler-D. Doe. | Donkeyman-S. Takayama. | Fireman -S. Tokuno. | Fireman -Y. Zeniya, | Fireman -M. Ikehata. |

| Fireman -E. Koyama | Fireman -T. Kimura | Fireman -D. Watanabe | Fireman -R. Sonoda, | Fireman -T. Sugihara, |

| Fireman -M. Hiratsuka, | Fireman -H. Haruda. | Fireman -K. Sugimura. |

Further Career:

Notable Events:

- During one exceptional voyage from New York to Europe on the 16th November 1928, the former President of the United States: Theodore Roosevelt and his family, would all take a voyage onboard the Homeric. This included Mr. and Mrs. Roosevelt, and their son Kermit Roosevelt as well as Mrs. Kermit Roosevelt. Kermit planned to travel from Europe all the way to India alongside and undisclosed brother for a big game hunt in Asia.

- Many other noteworthy people would take crossings aboard the Homeric during her service life life. These would include US Vice President to Calvin Cooidge: Charles G. Dawes and Mrs. Dawes on November 9th 1929, IMMC director Philip E. Curry, financier J. P. Morgan, ballet dancer Anna Pavlova, Irish President William T. Cosgrave, future Prime Minister of the United Kingdom: Sir Arthur Balfour, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland Earl John French, Film Director David Wark Griffith, George F. Baker, US Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, Sir Henry Lunn, composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, Colonel Edward M. House, and many others.

- On August 18th 1922 shots were fired when the Homeric docked in New York. This was due to a small motorboat which suddenly arrived and docked on the pier near Homeric. Customs guard Charles Ostman suddenly sighted several of the seven-man gang aboard the ship run across the pier into the Homeric. They then emerged, their coats bulging with smuggled alcohol and jumped off the pier back onto their ship which then sped away. Ostman fired several shots which went over their heads, and crew members from the Homeric were furious with shouts of: “We’ll get you for that!”. Two waiters aboard the Homeric were later arrested as they had been the concealers who handed off the two dozen bottles of whisky to their co-conspirators who boarded the Homeric and then escaped on their craft.

- In November 1922, a young 22-year old Czecho-Slovakian man named N. Y. Felix Gulej jumped off the gangplank of the Homeric as an attempted suicide. This was due to him having landed in America just two weeks earlier and secured a job, only to be deported due to him being illiterate. Gulej wrestled free from his two officials taking him aboard the Homeric and dove into the water between the pier and the liner. He was rescued – unonscious, by two longshoremen and immediately taken to Homeric’s onboard hospital and revived. He was then successfully deported.

- In December 1922 the Homeric came within 200 yards of an unexploded German mine when approaching Southampton. Thankfully the ship was safe and the mine was destroyed by British destroyers.

- The Homeric was the first White Star Line ship to abloish the decades-long tradition of the Smoking Room being a male-reserved space with women forbidden. At midnight on the 13th August 1926, the Homeric departed New York but the sign outside her First Class Smoking Room forbidding women from entry was gone. For the first time in the company’s entire history, women were permitted to partake in the card games, tobacco and other ammenities of this room as times were now changing.

(Author’s Collection)

Accidents:

- On the 12th February 1923, whilst on a cruise from Syracuse to Alexandria, the Homeric had a collision with an unidentified brigantine off the coast of Turkey. The damage caused included Homeric’s gangway ladder being torn away and some of the second class deck windows being shattered.

- On the 16th February 1926 during another cruise, the Homeric struck the British steamer Charterhurst with her bow and lost her starboard anchor in the process. Charterhurst fared much worse and had to be beached soon after.

- On the 9th July 1927 the Homeric ripped the masts off the Italian schooner Giacomo whilst entering the English Channel. Homeric was undamaged and left one lifeboat with the Giacomo before proceeding.

- During a westbound crossing on the 26th November 1928, the Homeric was wrought by an extremely serious gale. The weather smashed in the hatch of cargo hold no.2, and water damaged some cargo. The forecastle head railing was then torn away and the windows of the First Class promenade at the base of the forecastle were shattered.

- On June 5th 1929 the Homeric collided with the White Star tender Traffic whilst receiving mail and passengers in Cherbourg. Homeric was undamaged but Traffic bumped her starboard quarter into the big liner and suffered two damaged plates and a broken railing.

- On the 27th September 1932 the Homeric seriously damaged the Spanish liner Isla de Teneriffe very ironically whilst the latter was departing the very island she was named after. Homeric severely twisted the stem of the Spanish vessel, but was still able to continue her own voyage.

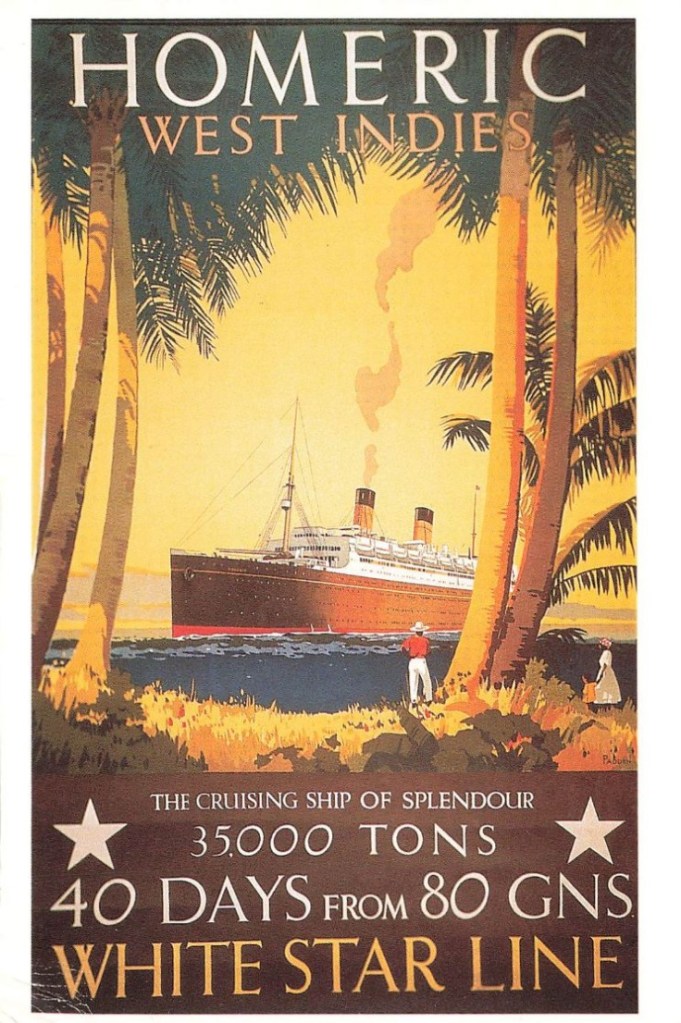

An Opulent Cruise Ship

In 1929 the Wall Street Crash occurred, which subsequentially led to the Great Depression. Crossing the Atlantic was suddenly unaffordable for many, and shipping lines struggled to operate. One venture that could still bring in money was budget-cruising. Cruising had been a minimal market for several decades at this point, but now things were to change. White Star Lines “Big Three” were all struggling with Homeric being hit especially hard. White Star had been planning a 25-knot liner as soon as 1926 to replace her. That was ordered in 1928 as Oceanic. But Oceanic never came to be, as White Star hadn’t the funds and instead built the smaller and economic twins Britannic and Georgic. Homeric truly didn’t have a place on Atlantic service now, and was taken off permanent with her last departure from New York being on June 1st 1932.

White Star was not done with Homeric yet however, and had her refitted for full-time duties as a cruise ship. One of the most significant changes was her Third Class had been completely renovated with much better facilities, reducing the count from 1750 to 659. Second Class was abolished and became Tourist Class. Emigrant carrying was no longer needed due to law changes in the US, and now the experience for all passengers on board was improved. Homeric was now sent on cruises to the Mediterranean with stops in the Canary Islands, Constantinople, Casablanca, Morocco, Gibraltar, Algiers, Sicily, Monreale, Naples, Funchal and the Madeira Islands. Homeric’s speed that had always hindered White Star’s timetables was now perfect as well as economic, since now passengers wanted to be aboard as long as possible.

And surely they did as Homeric was truly an exceptional cruise ship. She had always had a wonderful, quiet atmosphere on board as “The Ship of Splendour” and her accommodations were fantastic. This ship garnered amazing popularity and could carry 472 First, 832 Tourist and 659 Third Class. In winter, she cruised to the West Indies. Impressively Homeric fared even better than her running mates and won money back whilst others lost it during this time period.

As was always, things weren’t to last and going further into the 1930’s, the ship began to lose money as newer competition made her obsolete. Her age was also quickly catching up with her as the ship suffered from hull cracks and general wear, as so much time had passed from starting construction to entering service. White Star had merged with Cunard in 1935, and the new company was keen to offload unprofitable excess tonnage. By July, Homeric would receive her last master: Captain Peter Vaughan of the Aquitania. There was gloom amongst White Star’s officers and personnell that Olympic was doomed to be sent to the breakers soon and that Homeric would follow before the end of the year. Majestic had also been condemned as she was to be replaced by the new superliner RMS Queen Mary the following June.

The Silver Jubilee Fleet Review:

Despite concerns ever growing among the crew that the Homeric would soon be done for, the ship was still ready for one last hurrah. On April 5th 1935 it was announced she had been specially picked to be the principal sightseeing ship for visitors attending King George V’s annual Silver Jubilee Fleet Review. On July 15th Homeric left Southampton and took up her position in Spithead amongst the countless warships, destroyers, hospital ships, submarines and even the then-largest battleship in the world at the time, HMS Hood. This colossal fleet including Homeric was about 157 ships strong. The next day she sailed with the fleet towards the open sea, led by the King. Another main ocean liner attending with her was Cunard White Star’s Berengaria, -the former Imperator. The two ex-Germans were both given one last moment of great glory in this massive display of Britain’s naval prowess.

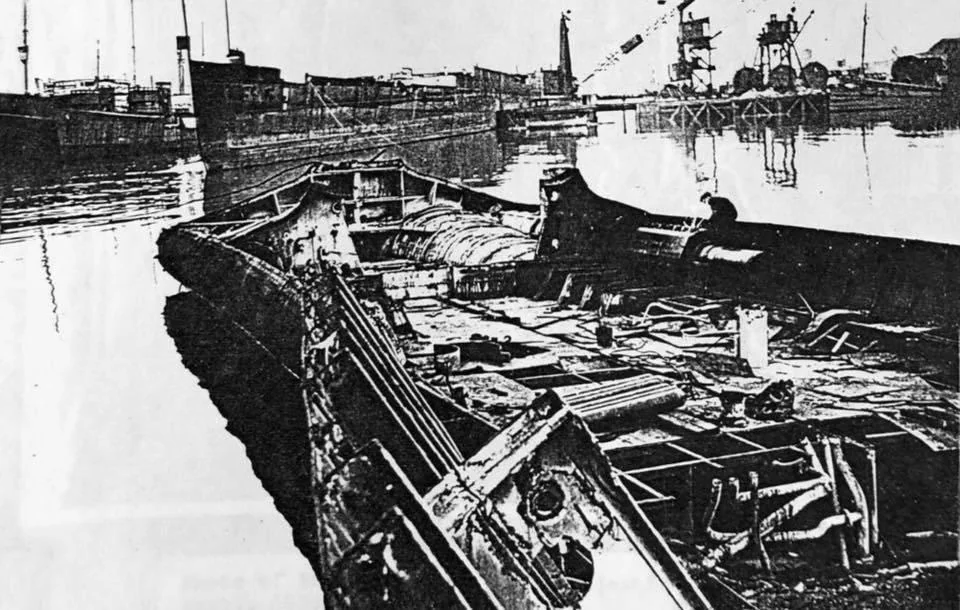

Sadly this final four-day voyage would prove to be too short. With the last hurrah finally over, Homeric sailed back to Southampton towards a very disheartening future. She would only have one more month of service as a passenger liner. And just with that, she was retired in September 1935 and laid up in Southampton. The rest of the “Magnificent Trio” was also out as Olympic had been laid up in April that year, and Majestic in February of the next.

The sad end of a beautiful vessel

Homeric was truly at the end. Olympic had been sold to the breakers in Jarrow the previous October. Homeric was put up for sale in February 1936 after being laid up off the Isle of Wight since October. Her sister, the Columbus was still sailing on cruises in popularity when Homeric was retired and there was consideration by German firms to buy her as well the RMS Laurentic and put them back on cruises. Another rumour the previous year had been that she and Olympic might be deployed as troop ships due to rising military tensions in the Middle East and Africa. Neither of these ever happened and a fortnight after being listed for sale, Homeric was sold for £74’000 to the Thos. W. Yard at Inverkeithing to be dismantled for good. In March she sailed under her own power to the breakers and was completely gone by the end of 1937. Homeric actually reunited with her old fleetmate Olympic at Inverkeithing in September, both were now just sad-looking double bottoms and were beached and completely scrapped not too far from one another:

The Homeric lives on

Unlike most ships which one sees pictures from decades ago and can only imagine what it was like to be aboard, that does not apply to Homeric. By incredible luck, a large assortment of her interiors is still viewable today. When Homeric was taken to Inverkeithing, her fittings were auctioned off into private hands – most never to be seen again, but a travelling showman by the name of John Edward Sheeran had other plans for some. He purchased the First Class Dining Saloon chandelier from a flea market in Kirkcaldy. He also bought much of the rest of the room including mahogany panels, pillars and even the staircase. Using these he furnished a 1914 cinema in Stonehouse, Scotland, that had once been named “The Palace” into “The Rex” at a cost of £1400 in 1937. This building is an absolute treasure trove of the former liner.

Though now closed today, evidence of Homeric is all around this building. The ceiling of her Dining Saloon and Chandelier, are perfectly preserved in place in the cinema with a stage below them. Other First Class panels adorn the rest of the room, being most similar to ones from the corridors and the First Class Lounge. Below them are undeniably the magnificent mahogany panels straight from the First Class Smoking Room. On either side of the stage are pillars from the Lounge. Light fixtures resembling those in the Lounge and Corridors are also within the building. The stairs leading up to the balcony are none other than the Grand Staircase of the vessel, now painted a lighter colour. These treasures and likely many more, ensure that Homeric still lives on ninety years after being dismantled.

Conclusion

As is evident, RMS Homeric was still a special and well-liked ship despite all her faults. She only ever really had proper glory and success in scattershot moments as her actual sailing career was extremely inconsistent. Sometimes Majestic would carry more passengers in First Class than Homeric carried in all three, so no wonder White Star wanted an equal replacement. Nonetheless, the RMS Homeric still has her fans and is near-unanimously agreed to have been a true floating palace, inside and out, back in her day and by those who learn about her today.

Bibliography

- J. H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes September 1963 “Homeric”, ex- “Columbus” of 1913 p. 175 – 178

- (1922) HOMERIC AT SOUTHAMPTON , p. 11 Accessed: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1922/01/21/98972968.html?pageNumber=11

- The Nautical Gazette v.102 (1922) p.597, Accessed: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c2603271&seq=546&q1=homeric

- The New York Times (1921) NEW HOMERIC DUE FEB. 23 p.4 Accessed: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1921/11/27/113324023.html?pageNumber=4

- The Nautical Gazette v.102 (1922) p.278, Accessed: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c2603271&seq=258&q1=homeric

- Marine Engineering & Shipping Age 1924, Volume 29 Accessed: https://archive.org/details/marineengineeri271922phil/page/171/mode/1up?view=theater

- The New York Times (1922) BIG HOMERIC MAKES STORMY FIRST TRIP , p. 6

- The New York Times (1922) NEW LINER HOMERIC STARTS FOR NEW YORK , p. 11

- The New York Times (1922) HOMERIC HAS A ROUGH TRIP , December 18th, p.8

- The New York Times (1922) 1,600 VISIT THE HOMERIC.; Five-Room Suites With Private Decks Centre of Interest. February 26th, p.20

- The New York Times (1921) BUYS GERMAN LINER.; Mercantile Marine Company Adds the Columbus to Its Fleet. June 25th, p. 11, https://www.nytimes.com/1921/06/25/archives/buys-german-liner-mercantile-marine-company-adds-the-columbus-to.html?searchResultPosition=80

- https://www.nytimes.com/1922/02/26/archives/1600-visit-the-homeric-fiveroom-suites-with-private-decks-centre-of.html?searchResultPosition=12

- https://www.nytimes.com/1925/04/22/archives/japanese-ship-sinks-with-a-crew-of-38-liners-unable-to-aid-homeric.html?searchResultPosition=44

- (1989) Eaton, John P. , Falling star : misadventures of White Star Line ships, Patrick Stephens Ltd

- Braynard, Frank O. (1982) Fifty famous liners : W.W. Norton , New York

- Marine engineering & shipping age v.29 1924 : Accessed: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015080127551&seq=270

- (1922) CARRIES USUAL STOCK OF LIQUOR, Rushville Daily Republican, October 11th, p.1 https://archive.org/details/rushville-daily-republican-1922-10-11/mode/2up?q=homeric

- Engineering 1922-02-17: Vol 113 Iss 2929, Accessed: https://archive.org/details/sim_engineering_1922-02-17_113_2929/page/208/mode/2up?q=homeric

- The New York Times (1922) THREE MEN HELD IN BIG WHISKY PLOT, August 18th, p. 15 https://archive.org/details/sim_new-york-times_1922-08-18_71_23582/page/n13/mode/2up?q=homeric

- The Northwestern Miller 1922-11-22: Vol 132 Iss 8, Accessed: https://archive.org/details/sim_northwestern-miller_1922-11-22_132_8/page/850/mode/2up?q=homeric

- (1928) MR COSGRAVES TOUR, The Irish Times, January 12th, p.7 https://archive.org/details/per_irish_times_1928-01-12_70_22069/mode/2up?q=homeric

- J. Gregory, Mackenzie : Ahoy – Mac’s Web Loghttps://ahoy.tk-jk.net/macslog/SilverJubileeReviewoftheF.html#:~:text=I%20recently%20received%20from%20a,Surveying%20ships%2C%20and%20Training%20ships. (Accessed Septmeber 2025)

- https://archive.org/details/per_new-york-times-magazine_the-new-york-times_1923-08-26_72_23955/page/n4/mode/1up?q=Homeric+splendour

- Perry Record (1922) On board the White Star Liner “Homeric” , 27th July, p.1 https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=pr19220727-01.1.1&srpos=21&e=——-en-20–21-byDA-txt-txIN-liner+homeric—-1922—–

- The Evening World (1922) ORDERED DEPORTED AS ILLITERATE ATTEMPTS SUICIDE, 11th November, p.2 https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=tew19221111-01.1.2&srpos=37&e=——-en-20–21-byDA-txt-txIN-liner+homeric—-1922—–

- https://www.nytimes.com/1929/09/15/archives/believe-marks-drowned-homerics-officers-think-ohio-man-fell.html?searchResultPosition=26

- https://www.nytimes.com/1922/05/05/archives/earl-french-here-on-a-flying-visit-first-british-commander-in.html?searchResultPosition=11

- https://www.nytimes.com/1932/11/20/archives/when-hoover-and-roosevelt-met-before-their-first-association-was-in.html?searchResultPosition=66

- https://www.nytimes.com/1921/06/26/archives/olympic-departs-with-2031-aboard-liner-leaves-with-largest-overseas.html?searchResultPosition=2

- The Advertiser-Journal (1926) White Star Line Yields to Women and Throws Open Smoking Room, 14th August p.6 https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=adv19260814-01.1.6&srpos=24&e=——192-en-20–21–txt-txIN-liner+homeric—-1926—–

- The Long Islander (1928) Roosevelts Sail For Big Game Hunt, 6th November p.19 https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=lir19281116-01.1.19&srpos=8&e=——192-en-20–1–txt-txIN-liner+homeric—-1928—–

- The Daily Press (1929) AMBASSADOR DAWES SAILS, 9th November p.2 https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=tdp19291109-01.1.2&srpos=1&e=——192-en-20–1–txt-txIN-liner+homeric—-1929—–

- https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=anw19250502-01.1.1&srpos=6&e=——192-en-20–1–txt-txIN-liner+homeric—-1925—–

- https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=rpj19250424-01.1.1&srpos=8&e=——192-en-20–1–txt-txIN-liner+homeric—-1925—–

- https://www.nytimes.com/1925/04/22/archives/japanese-ship-sinks-with-a-crew-of-38-liners-unable-to-aid-homeric.html?searchResultPosition=3

- https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/556097336/?match=1&terms=homeric%20liner

- https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/544586062/?match=1&terms=homeric%20liner

- https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=FHD19220224.2.19&srpos=1&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN-homeric——-

- https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=MMH19220312.1.20&srpos=37&e=——-en–20–21-byDA-txt-txIN-homeric+liner——-

- https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=MMH19220331.1.10&srpos=44&e=——-en–20–41-byDA-txt-txIN-homeric+liner——-

- https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SLODT19220821.2.58&srpos=25&e=——-en–20–21-byDA-txt-txIN-homeric+knots——-