SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse – “Der Große Kaiser”

| Name | SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse |

| Operator | Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen |

| Yard Number | 234 |

| Code Number | QGLF |

| Builder | AG Vulkan, Stettin |

| Launch Date | 4th May 1897 |

| Maiden Voyage | 12th September 1897 |

| Tonnage | 14’349 GRT 6’400 NRT |

| Length | 197.7 meters |

| Width | 20.13 meters |

| Draught | 11.90 meters |

| Installed Power | 27’000 hp |

| Maximum Power | 31’000 hp |

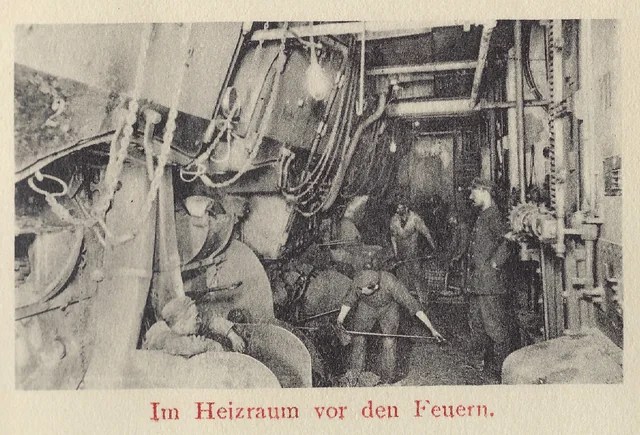

| Propulsion | 2 triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 22 knots service (41.67 km/h) 23.59 knots max (43.69 km/h) |

| Crew | 488 |

| Passengers | 1st Class: 206 2nd Class: 226 3rd Class: 1074 |

| Construction Cost | $2.7 million (1895) 4.5 million marks |

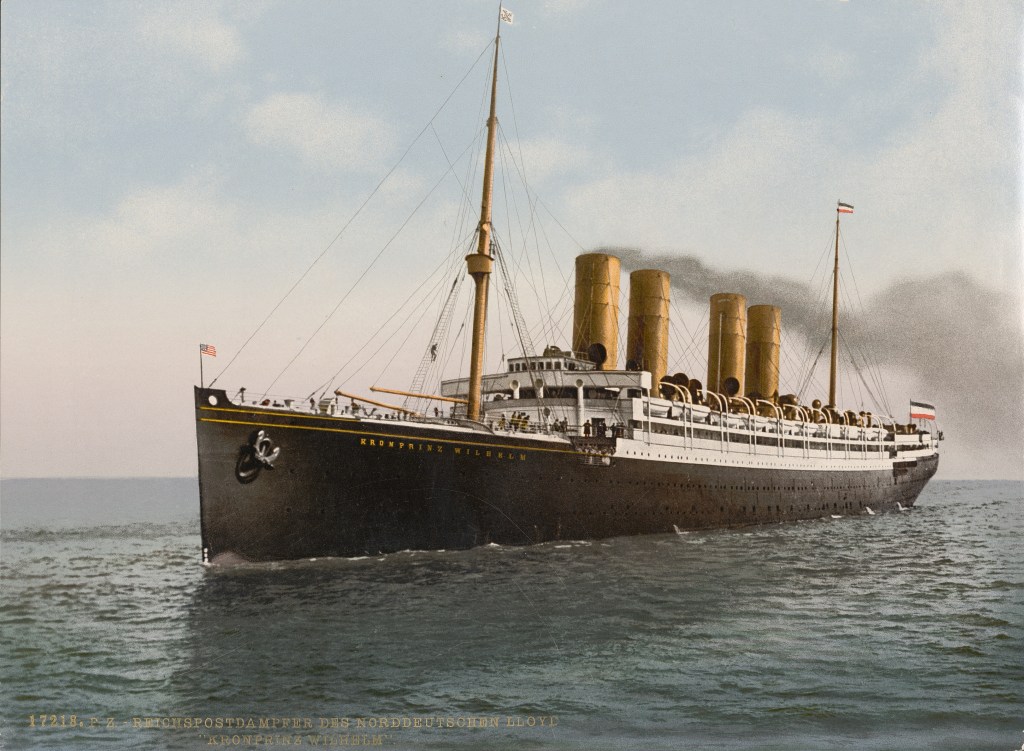

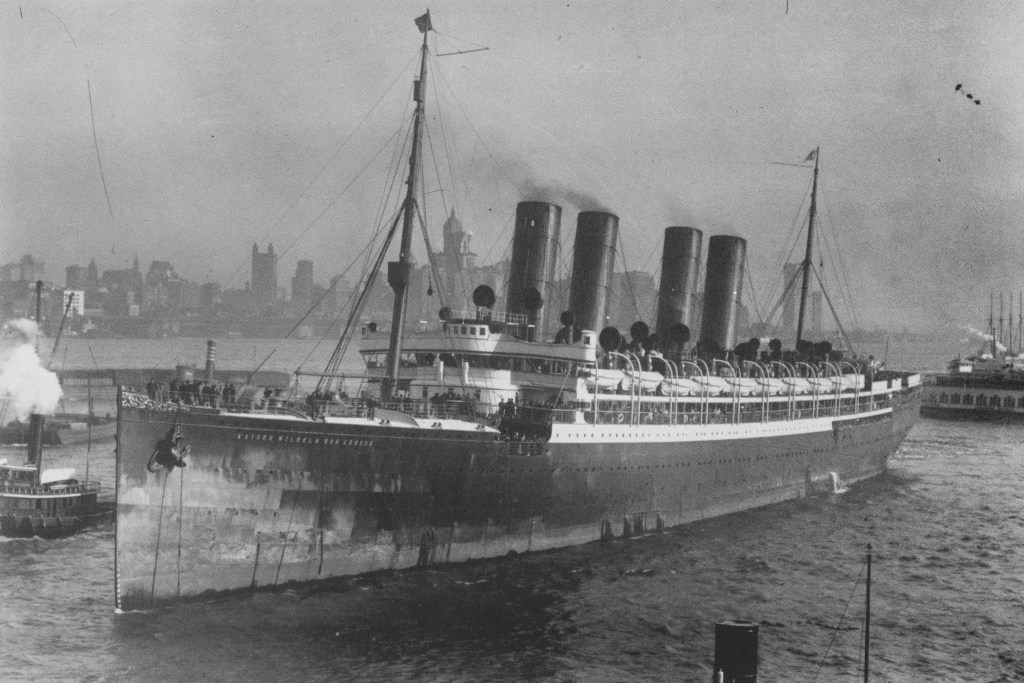

SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse is considered by many to be the world’s first true superliner. As in a most modern ship that held the three signature aspects of being fast, luxurious and huge. Launched in 1897, she was Germany’s first major contender for the entirety of the transatlantic trade, and set down the blueprints that led to a race between nations. creating many of the greatest and most famous ships in history. Even as just the first, this vessel still wrote an incredible, daring story over her seventeen years at sea.

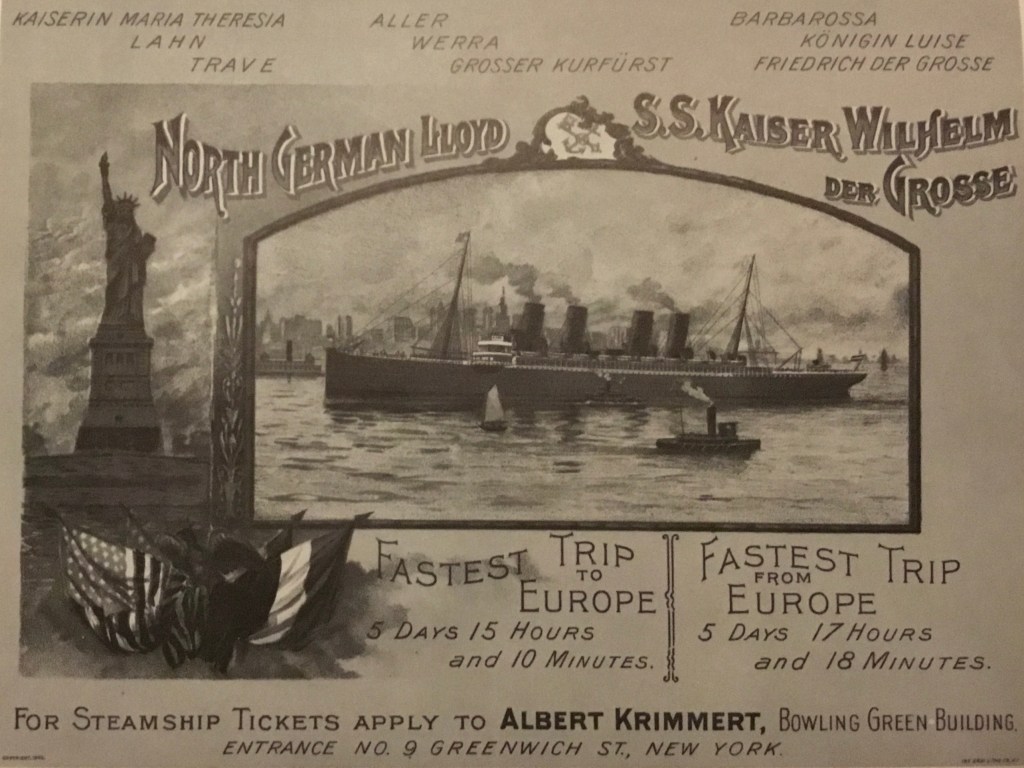

Transatlantic Travel up until that point

The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse being built in 1897 was not some big lucky one-hit-wonder for the North German Lloyd. Instead it was a ten-year project Lloyd had been working on to put themselves at the top. They were quickly becoming notable more and more during these years, from 1881 – 1891 they ran the largest international fleet in the world aside from Britain. Their services consisting of eleven ships, the Flüsse Class with the first being Elbe (1881), Werra (1882) and Fulda (1883). All of these ships very much had the potential to win the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic, for the first time by Germany as only Britain and America had ever held that prestige.

None of the Flüsse Class was ever able to hold the record, but they very significantly made Lloyd the largest international shipping line as mentioned, and these eleven ships carried more passengers into New York than any other. They truly were the definition of Schnelldampfer (Express Steamer) with two departures weekly that Lloyd would improve on further. They very carefully laid down the blueprint of being extremely luxurious too for the time, which would garner them international popularity.

The mastermind behind the Flüsse Class was Lloyd Director, Lohmann. When he passed away, he was succeeded by new Director Heinrich Wiegand who was in a difficult position as leader now. The Flüsse Class represented the largest fleet of express mail steamers in the world, but Lloyd’s biggest rival: HAPAG (Hamburg American Line) was building quickly a modern fleet of their own twin-screw steamers as opposed to the Lloyd’s single-screw Flüsse Class. Lloyd’s leading position was on the line and Wiegand was determined to make the next great leap forward for the company. He worked with Chief Engineer Max Walter on the specifications for a new kind of liner – a superliner. Lloyd sent agents to the great shipyards of Belfast, Glasgow and Newcastle to recruit designers and engineers and craftsmen. Once all the modern British shipbuilding methods and designs were learnt and improved, 1895 was the time to act.

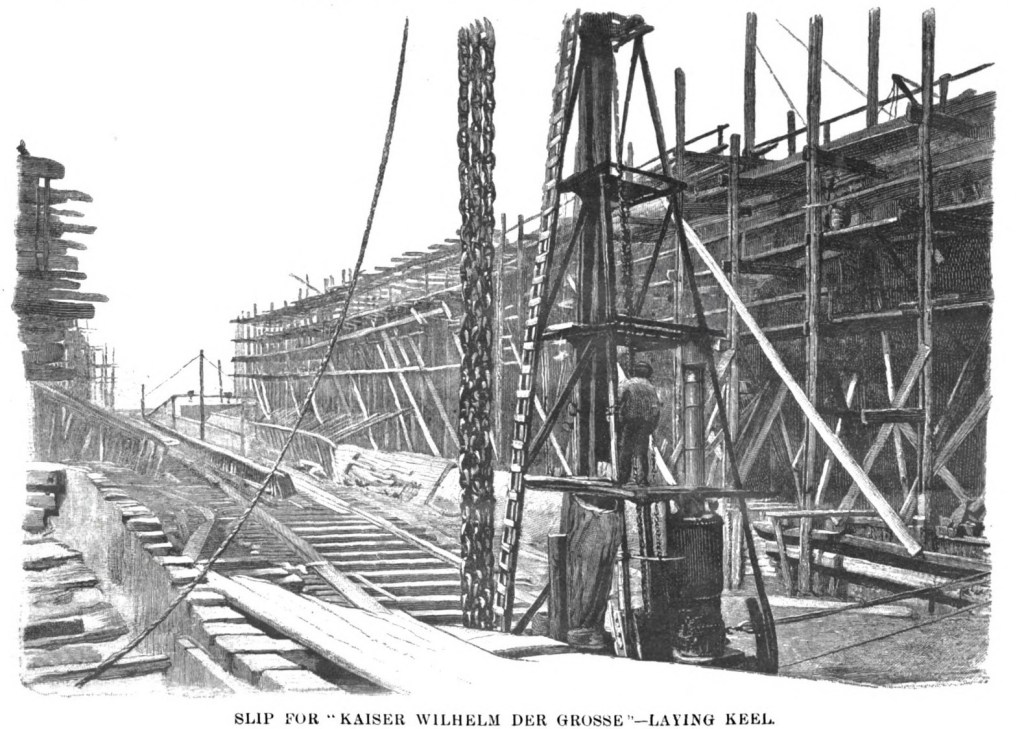

It was this year that Wiegand would order two colossal steamers that would come to be known to the world as Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and Kaiser Friedrich, both from German shipyards with the former from the Vulkan Werft in Stettin and the latter from F. Schichau in Danzig. They would be built with the very best possible technologies at the time. They would completely stop HAPAG in their tracks, completely outsize the largest British steamers at the time, and likely snatch the Blue Riband too. Lloyd would become not only the most premier German line, but the greatest international one too, and this honour would be bestowed to Germany alone. This is what Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse would represent.

Common misconceptions

The ideas and support behind the creation of the first German superliner and its subsequent sisters is often subject to misinformation, namely involving the support of Kaiser Wilhelm II and state subsidies being given to German shipping lines. The first with Kaiser Wilhelm II, is often attributed that he was a leading figure behind the construction of Germany’s high-speed liners. There is a prominent story that after touring the RMS Teutonic in 1889 and admiring its auxiliary cruiser fittings, he then discussed with his admirals that Germany needed these too. The German high-speed liner project had already been started in 1887 when Hapag started working on the Auguste Victoria Class. Wilhelm was a keen maritime enthusiast, and closely connected with leading figures in both Hapag and Lloyd, but he never had a role in the decision-making between the companies and more so helped settle disagreements between the two frequently clashing companies. There is not a single bit of evidence that Wilhelm encouraged shipping lines into new building programmes for liners, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse received absolutely no state subsidy and was the bold decision of Director Heinrich Wiegand to outclass Hapag’s Auguste Victoria class and compete with Cunard’s Campania and Lucania.

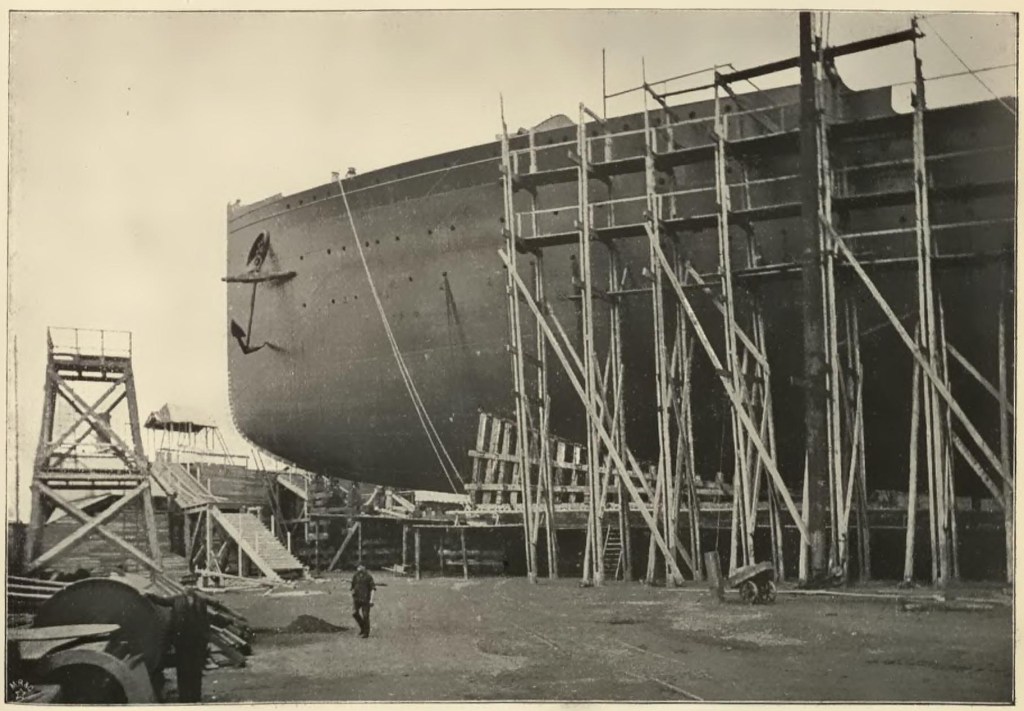

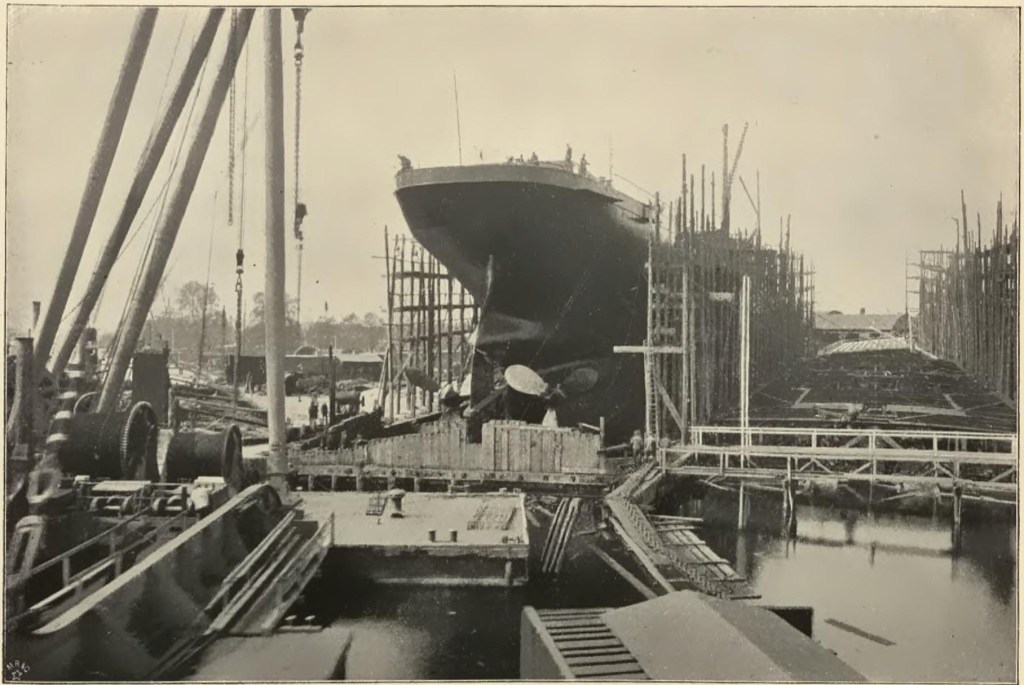

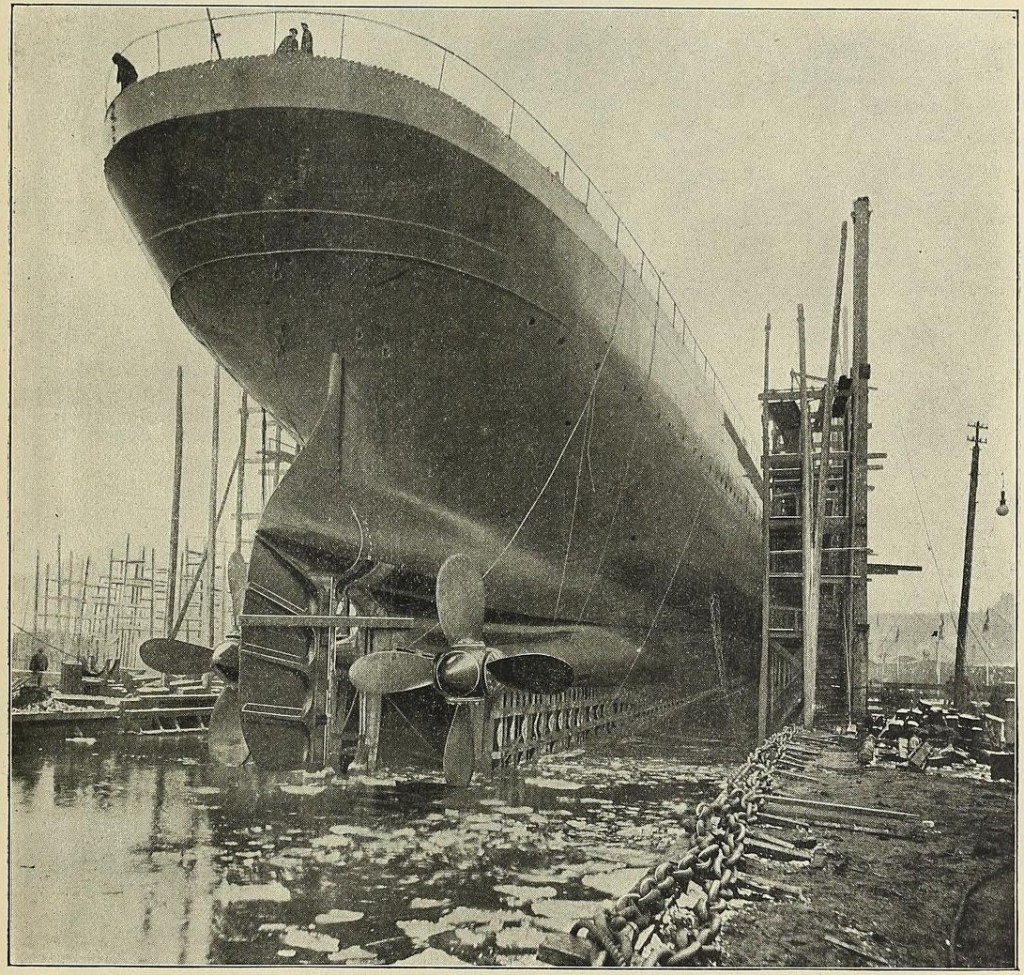

Designing and Building the Superliner

Right on the day the North German Lloyd commissioned this vessel, their contract with the Vulkan Werft in Stettin very specifically stated that this vessel must have a service speed of 21 knots, to compete with Campania and Lucania. Despite the record that this vessel was very famous for, amazingly she was not designed with full intention of taking the Blue Riband, but rather mere competition and to outclass those two previous Cunard steamers. When calculating the speed expected, it was more so to ensure a six-day voyage from Bremerhaven – New York. This way the twin Kaisers would arrive during the day, beneficial as passengers were unable to be processed at night. In order to reach this goal, the designers foresaw that a horsepower of 27’000 was required minimum, which was approximately 3000 horsepower less than Lucania, current holder of the Blue Riband. In addition, the Lloyd steamer was to be about 1700t greater than her British contemporaries which was why nobody in Germany at the time expected Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse to take the Blue Riband.

Features of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse

Construction

The Launch

(Author’s Collection)

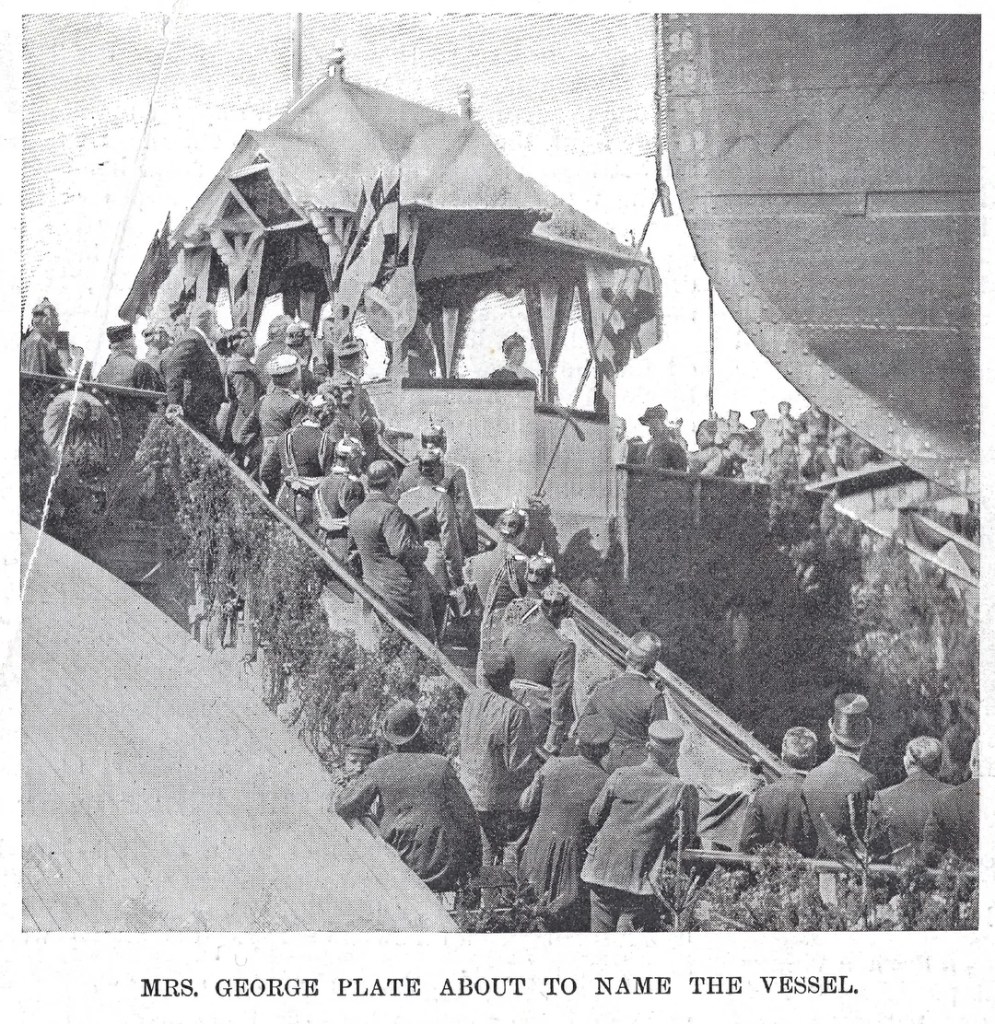

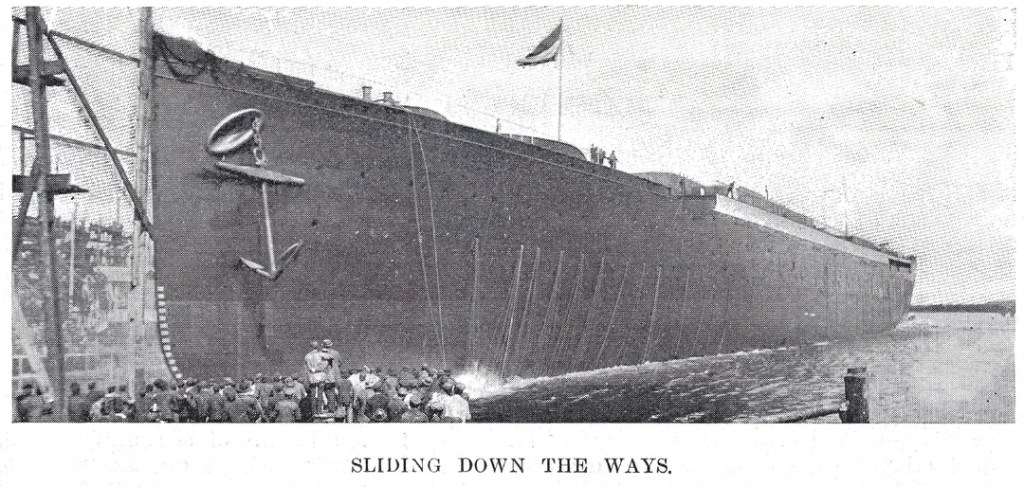

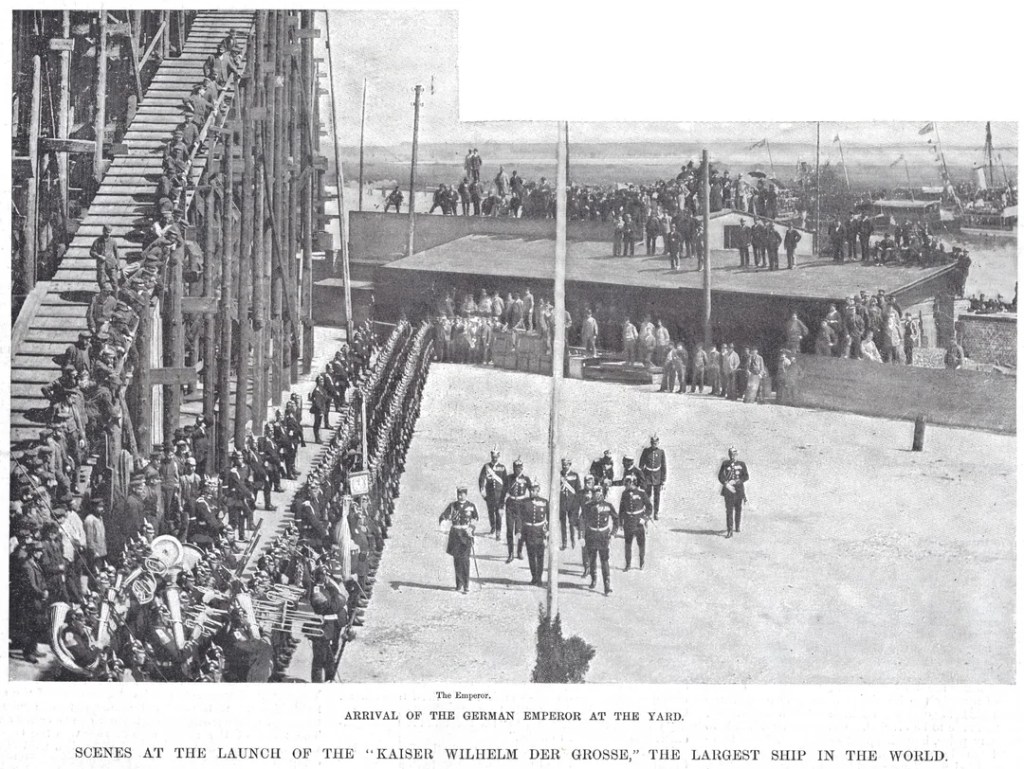

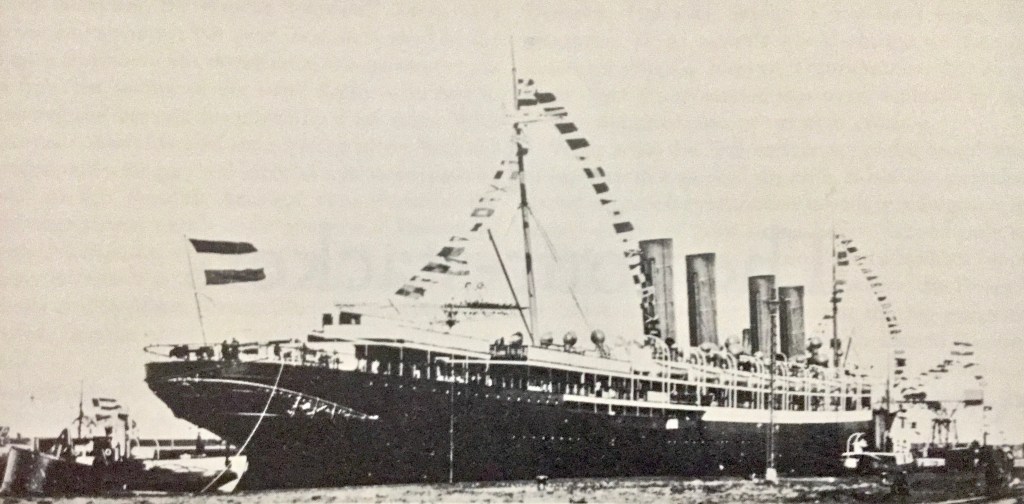

It was the 4th May 1897 in the Vulkan Werft of Stettin, located in what is now Poland. Today was essentially a public holiday. Schools had closed, the streets were decorated fit for a festival, and the entire population was up and outside. They streamed in droves through the gates of the shipyard carrying blue flags and garlands. The world’s largest ship was lying right in front of them. And on a podium right in front of the bow of the great vessel was his Imperial Highness, Kaiser Wilhelm II. It was not often that the reigning head of the German Empire had left the capital city, but today was special. He had arrived on his own personal train, travelling to this port on the East Sea. And now standing in front of the ship finally with many high officials, it was time to begin.

A few minutes before the launch, the Kaiser greeted his officials as well as Frau Plate, who was a sponsor of the ship. The Kaiser gave a short speech to the masses, the concluding words were:

“I christen you with the name, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse!”

Sources conflict whether it was his hand or Frau Plate who released the wine bottle that smashed into the bow, giving signal, for the chocks to be knocked down, sending the great ship into the water. Over the next minute a deep rumble sent the ship stern-fist into her element for the first time, causing a mighty wave. When the ship was suspended with her bow on land and stern in the water, things were tense as that was when the ship was under the most stress. Thankfully the launch was a complete success. At this sight, those on land gave a massive “Hurrah!” that was heard all over the harbour. Germany had just launched the worlds newest ship, one that would soon appear in every newspaper at home, and around the world.

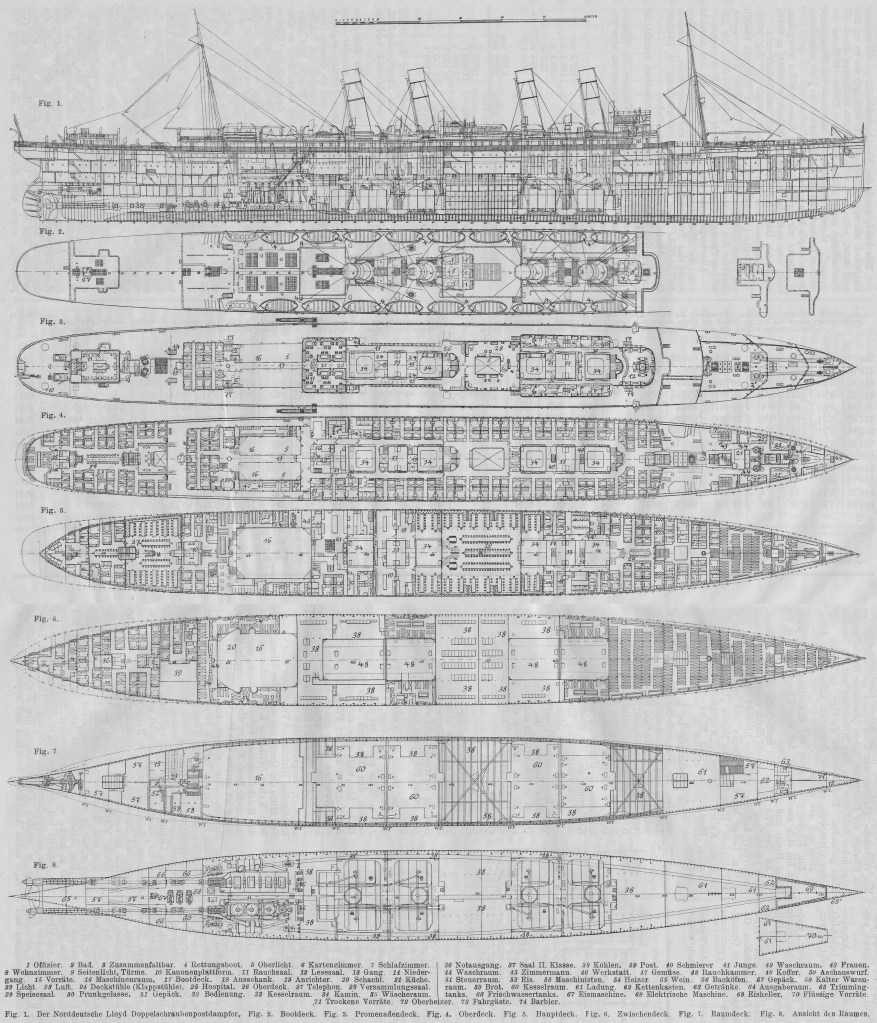

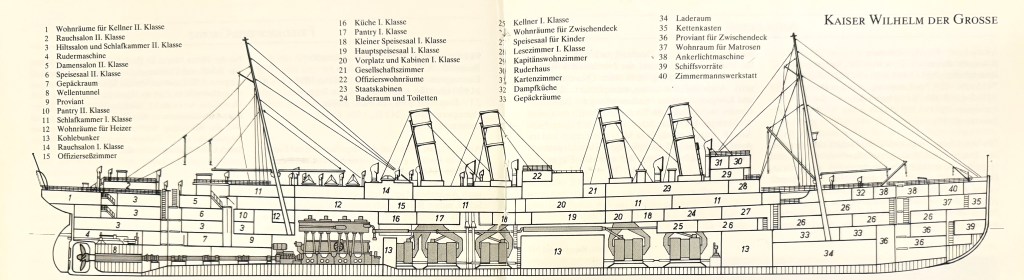

Deck Plans

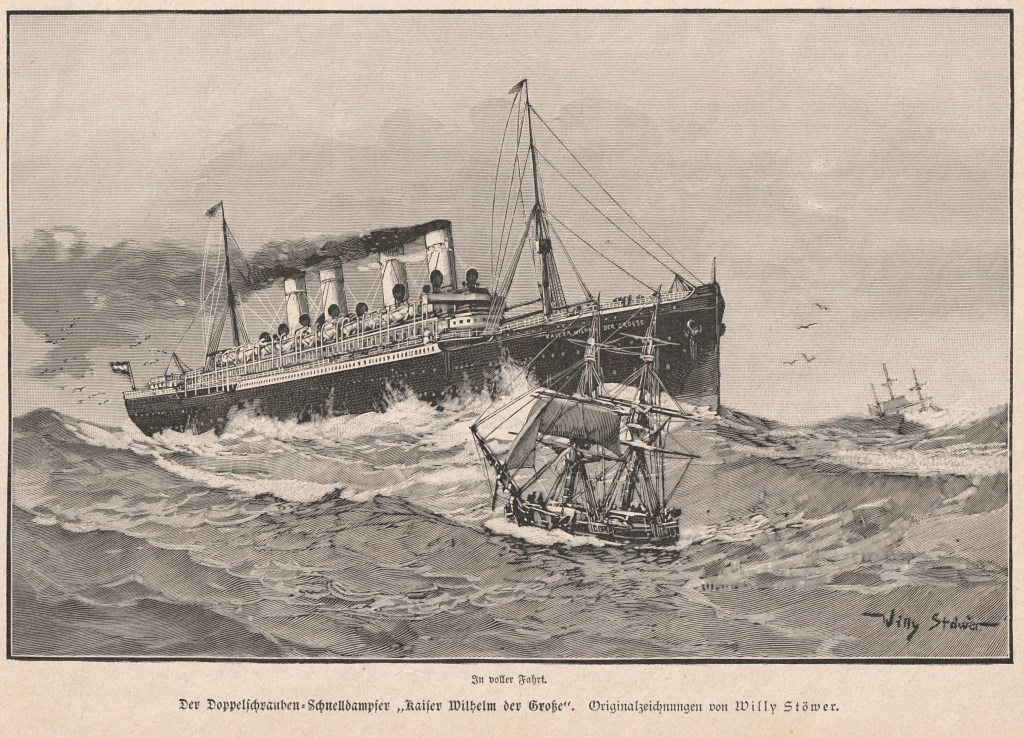

Setting sail for the Blue Riband

Things did not start out as planned, as the maiden voyage was delayed for a week when the Kaiser ran aground near Bremen. Despite the vessel not being expected to take the Blue Riband, the management of the Vulkan Werft waited anxiously for the results of the maiden voyage which occurred on the 19th September, ten days after the successful sea trials on the 9th. They as well as the world, was in for a shock. Due to the ship’s excellent machinery installation and hull shape she had sailed at a speed of 21.39 knots, clearly classing her at being able to take the Blue Riband, – especially as the ship’s engines were used hesitantly during the voyage, only generating 26’100 horsepower. On subsequent voyages this could be easily increased and that is exactly what happened. On the return maiden voyage back to Bremerhaven, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse took the eastbound Blue Riband off Lucania sailing at 22.33 knots, after having her power output increased by 1000 horsepower during this voyage. The ship caused such a sensation: the day after landing in New York, 40’000 people paid $1 each to tour the ship with all proceeds going towards charity. For the first time in maritime history, Germany had held the Blue Riband and on top of that it was tied to the world’s largest, most luxurious and soon-to-be most profitable ship. Slowly but surely, the performance of the ship was during her next voyages improved.

The further performances by the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse surprised even the engineers that built her. Already by her third return voyage from New York the ship was sailing at an average of 22.3 knots and of course taken the eastbound Blue Riband with it. Now the ship was sailing at an impressive output of 29’000 horsepower, never once having to exhaust the reserves. It was no wonder that the westbound would soon be hers too and the following year in March, the Kaiser snatched this record too off Lucania with a speed of 22.29 knots. The yearly average speed of the vessel over the following few years was recorded as: 22 knots during 1899, 22.2 knots in 1901, these being on average 1.5 knots faster than the Lucania on her individual voyages. Unsurprisingly, Cunard Line was completely beset at having been bested so unexpectedly. They tried everything on their side to outperform the Lloyd liner, but were unsuccessful. They had good reason to try besides the speed record, yearlong the Lloyd liner was almost always fully booked.

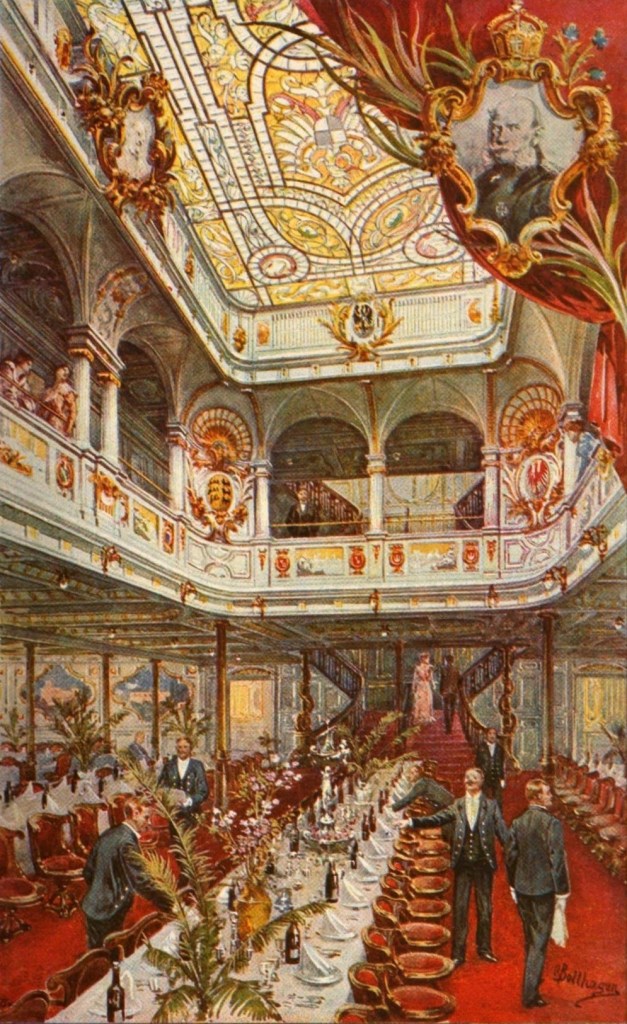

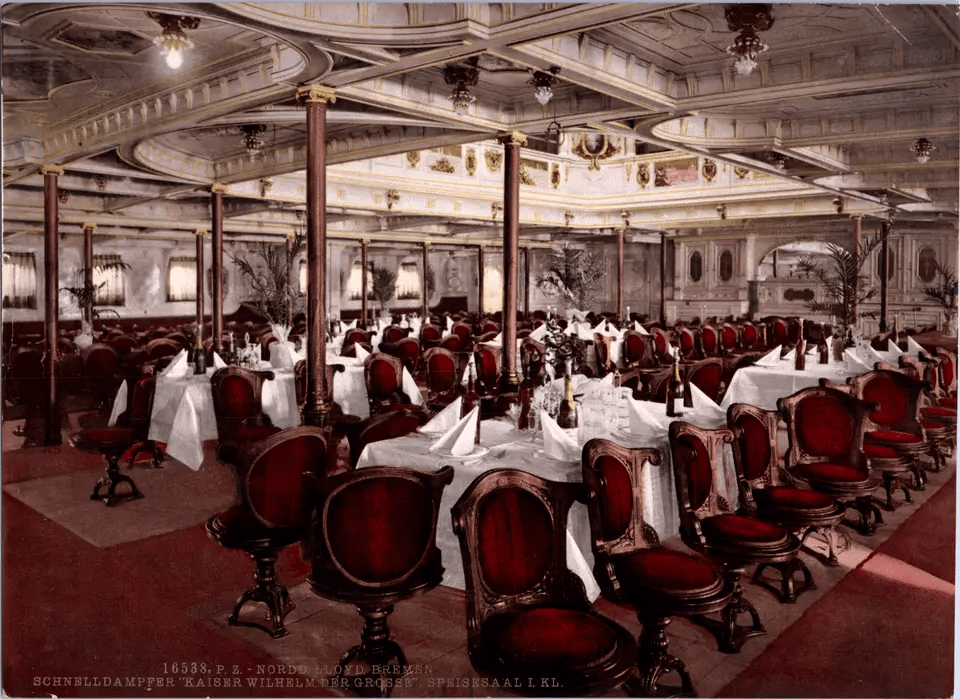

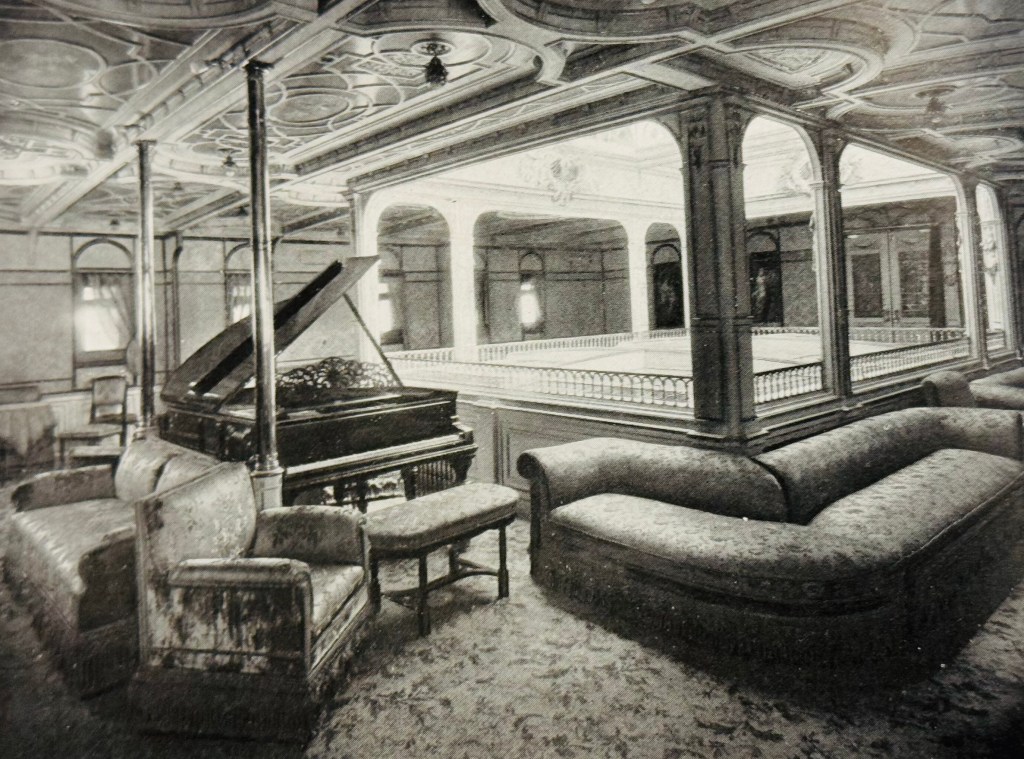

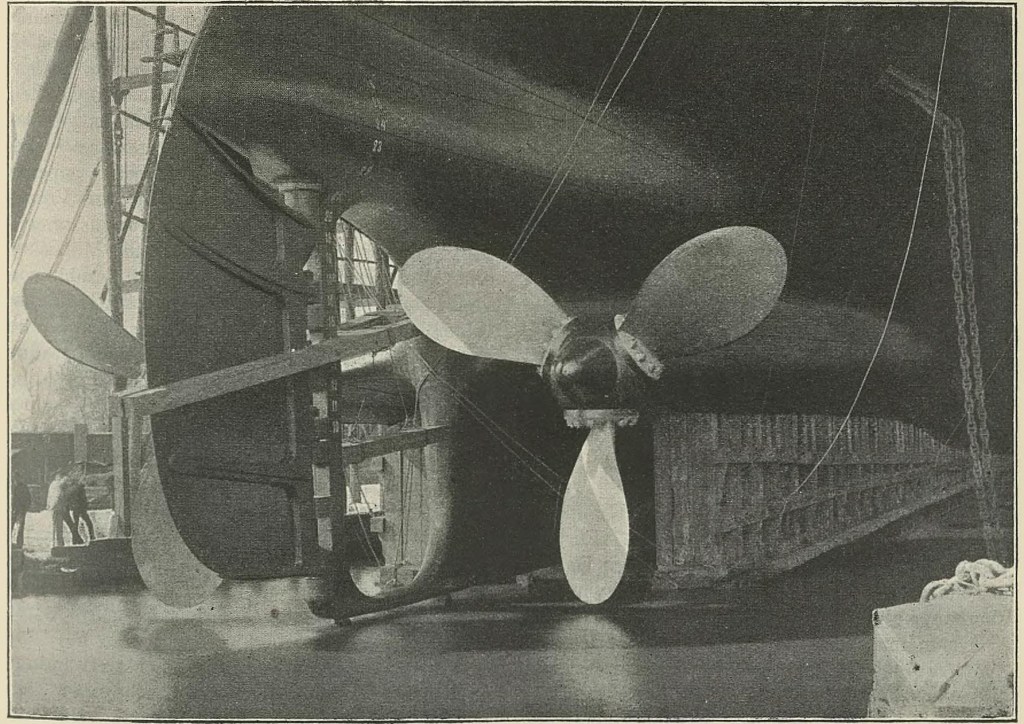

The Kaiser quickly established what was known as the nine-day boat. She sailed from Bremerhaven, to Southampton, to Cherbourg and then to New York with occasional calls in Plymouth. She was an absolute icon at home and abroad, the absolute pride of a nation. The Germans nicknamed her affectionately: “Der Große Kaiser” (The Great Emperor), and more humorously, “Dicker Wilhelm” (Fat Wilhelm). Abroad she was nicknamed “Rolling Billy”, because that extreme speed caused the ship to roll unfortunately, when crossing. The vessels outlandish and imperial interiors also gave rise to popular slang at the time. People would describe something as “Late North German Lloyd”, as in it was so ridiculously gilded and pompous, just like the interiors of the Lloyd steamer. Despite everything, “The Great Kaiser” was not perfect, having several problems during its first few years at sea. One of which was to do with the ships propellors: They each had a diameter of 6.8 meters. The stern of the ship was not wide enough for the turning circles of the propellors. They therefore had to overlap, with one slightly in front and the other behind. These uneven propellors also gave the ship noticeable vibration in her aft, likely the least-wanted characteristic for passengers. Fortunately swapping the three-bladed propellors for four-bladed ones eliminated this problem.

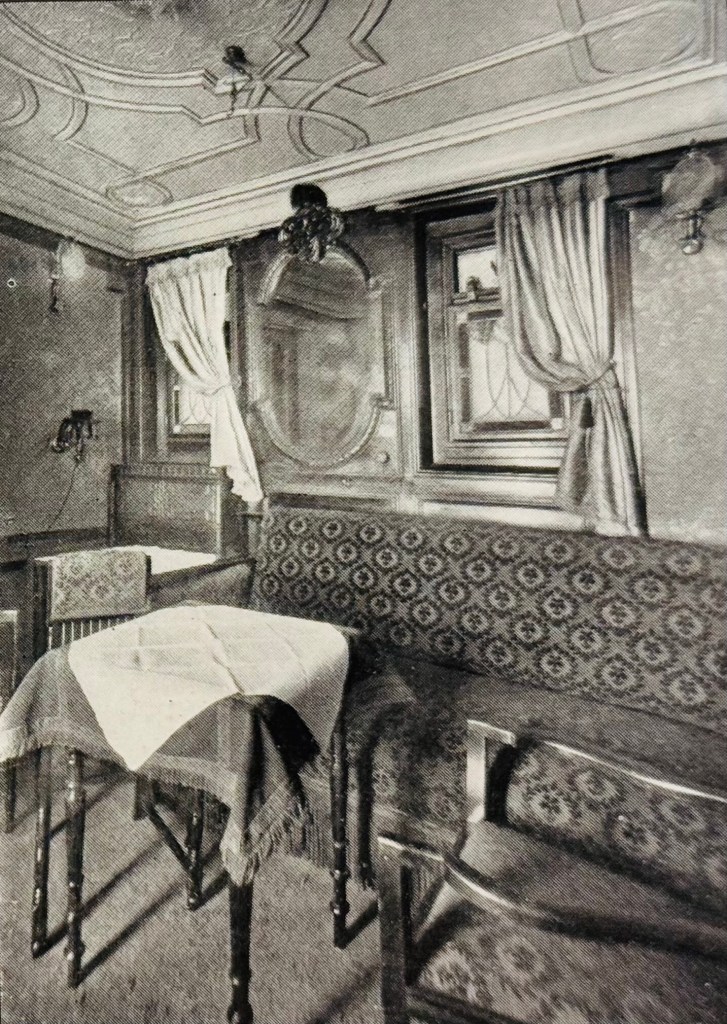

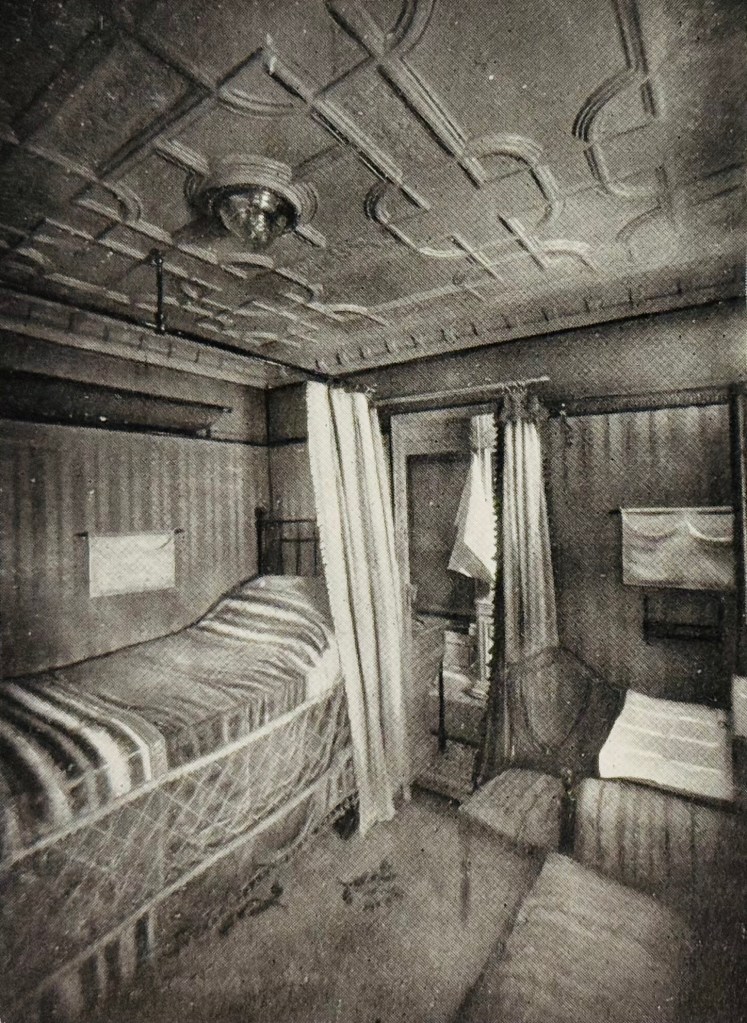

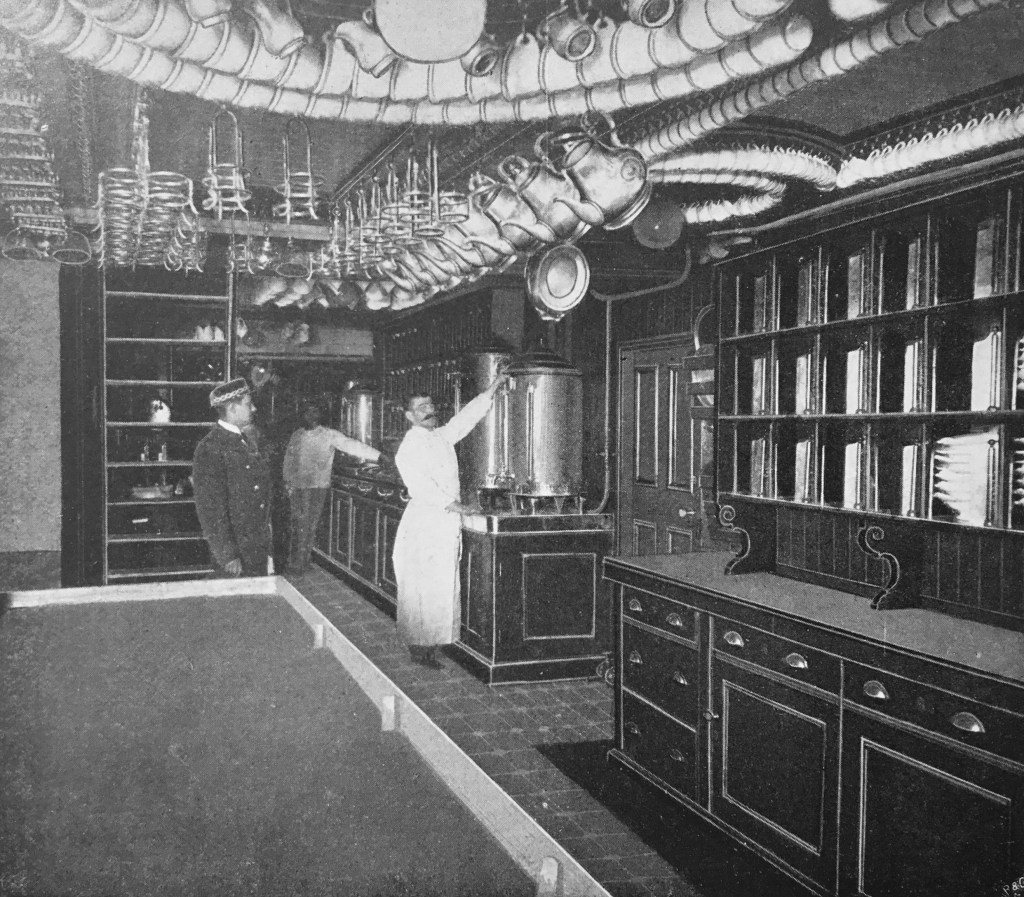

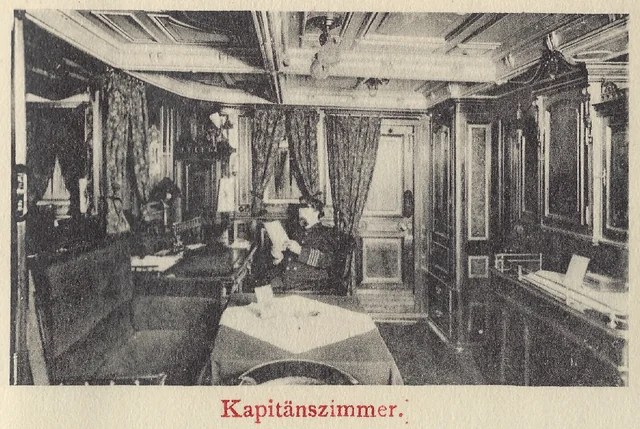

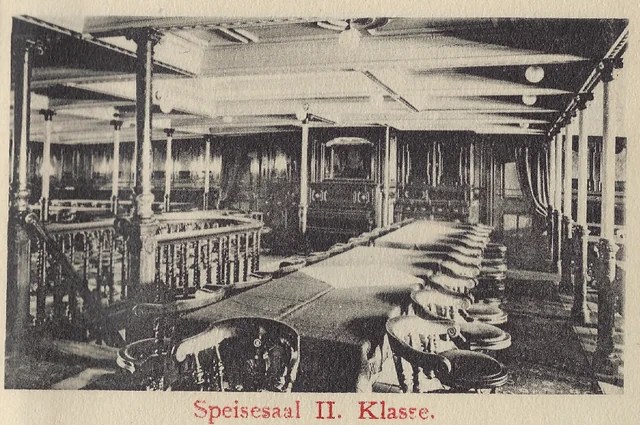

The Impossible Luxury of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, by Johannes Poppe

SS Deutschland, the unstoppable rival

The AG Vulkan shipyard only really needed to give minor tweaks or improvements to the ship again after her vibrations had been remedied. She had been a first-class success that brought nothing but praise and honour for her owners and themselves, a job well-done of the highest regard. This didn’t mean if another companies wanted them to do even better, they couldn’t. And Lloyd’s biggest rival had an offer for them..

As always, the one group in Germany that was unhappy with the success of the Kaiser was their biggest rival: Hamburg Amerika Line. The company was headed by mastermind Albert Ballin, who was actually disinterested in building high-speed express steamers unlike Wiegand. Ballin had commissioned the highly-successful Auguste-Viktoria Class express steamers during the 1890’s, and saw how quickly they became outclassed by the Campania and Lucania. Instead Ballin’s own motives for the industry was building larger and more comfortable ships, rather than the extremely expensive and rapidly-outclassed steamers of the Lloyd. Ballin had even been invited on a crossing aboard the Kaiser by Wiegand. Ballin was deeply impressed with the ship, and suggested to Hapag to build a larger, but slightly slower adversary. However, other higher-ups within HAPAG heavily disagreed: seeing the immense prestige and honour the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse carried, they wanted that off Lloyd and back onto themselves. That speed record was for everything or nothing. Thus, Ballin was ignored and Hapag representatives contacted the Vulkan Werft with the simple contract to build them a ship that outclassed Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in every regard. And they were soon to be delighted in 1900 upon receiving their ship:

(Author’s Collection)

On the 6th July 1900, the SS Deutschland sailed on her maiden voyage and stole the Blue Riband from the Kaiser sailing westbound at 22.42 knots. On her eastbound return, she took that record too at 22.84 knots. Out of the five, four-funnelled giants during the “Decade of the Germans” from 1897-1907, SS Deutschland would likely be the fastest by far to the extreme annoyance to the Lloyd. The Kaiser and the Deutschland even had an unofficial race in September 1900. The Kaiser left New York 1.5 hours ahead of the Deutschland, but Deutschland caught up and beat her to Southampton with an average speed of 23.36 knots. The Deutschland didn’t stay laughing forever as the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse pulled an astonishing 23.59 knots in June 1904 over a longer distance. The speed came at a big price, the Kaiser initially had vibration issues, but Deutschland could never lose hers. Deutschland could rattle so hard she once tore off her own sternpost and rudder, and had to be navigated back just using the propellors. This is why the Kaiser continued to be more booked-out than the Deutschland for years even after losing the speed record.

SS Kaiser Friedrich, the failed fleetmate

One might have already forgotten the second ship that Wiegand had commissioned alongside the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse back in 1895: the SS Kaiser Friedrich. This was exactly the fate this ship was to have: being quickly forgotten and left behind. The shipbuilders F. Schichau in Gdańsk, Poland had also built their own high-speed steamer that had been completed in 1898 to sail alongside the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse as part of a 2-ship weekly service, but that she only had 8 voyages under the Lloyd. The problem was simply that this fleetmate: the Kaiser Friedrich could not match the 22 knots and above speeds of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse.

Things were not planned to be this way: during construction the ship was planned to be about three quarters to a full knot faster than the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. This was due to F. Schichau applying their knowledge in building fast military destroyers into this passenger liner. Compared to the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse’s fantastic first crossing of 21.39 knots, the Kaiser Friedrich had sailed at a disastrous 17.73 knots and taken nearly 7.5 days to reach New York. A massive years-long scandal would ensue between the builders and the NDL over who was at fault and who had to take ownership of the liner, after a full year of tweaks and modifications failing to speed the ship up. Eventually the Lloyd completely threw the ship back into her builders hands who now were stuck with a ship with a very bad reputation. Her career would sadly never get better and she’d spend years being mothballed or sailing for very short charters under different companies.

The other German four-stackers

[i]

[i]

[i]

Coming Soon!

The Great Fire at Hoboken

It was the 30th June 1900. For the entire week, all of New York had been wrought by a severe heatwave. The nights were not any better. The sea winds only brought more hot air inwards to the city rather than ventilating it. It had been months since it last rained and it would be months until it rained again. The dryness across the entire harbour posed a severe fire hazard as the area was absolutely packed with wood: stairs, sheds, cargo, platforms, gangways and much more. Even the joints in the roofs of many buildings were filled with tar. This is where the ships docked, right next to warehouses and extremely unfortunately, where workers were loading thousands of bales of cotton. Everything could not have been set up more perfectly on that day, for an inferno to blaze. All it would take was one little slip for most of harbour to erupt into flame, as part of a massive chain-reaction.

It all happened as workers were loading cotton onto the ships at the North German Lloyd piers. Four ships were docked: SS Saale, SS Main, SS Bremen, and finally Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. The first three of the ships mentioned were freighters and that’s where the cotton was going aboard. the Kaiser thankfully had already offloaded her passengers and was being prepared for the return trip back to Bremerhaven. Suddenly the usual flow of work halted, and men began to run. The fire seemed to have started inside the warehouse sheds standing beside the Kaiser. A man was first seen carting burning cotton bales and dumped them into the water, but was hit by a huge cloud of smoke and the only real option was to run away. There were yells of “fire!” that quickly spread across Hoboken, but it was growing far too quickly, spreading across the bales inside the warehouse. The fire quickly reached unattended barrels of oil and turpentine which exploded. And just with that, in just nine minutes the fire spread from one building to the next, quickly consuming the NDL piers.

The fire bells quickly rang aboard the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse as the fire was raging on the pier beside the ship. The crew knew they had to get moving immediately to save the ship, and preparations frantically began. However the boilers of the ship did not have sufficient steam power to get moving and the ship was still firmly moored to the pier. This was absolutely instrumental as the hundreds aboard the ship were in grave danger and would be trapped if the ship couldn’t leave. The inevitable happened and the fire spread from a burning shed roof onto the Boat Deck of the Kaiser, quickly spreading thanks to material laying on deck. In an amazing act of self-bravery, one young officer sprinted down the gangway to the pier and operated the mooring winch to let the ship go. Not one moment too soon, as another shed near the Kaiser collapsed, sliding its roof onto the Boat Deck, worsening the blaze. Nearby, men were escaping the fire by plunging off the piers into the sea, and lifeboats were lowered from the Kaiser to help them. They were not the only ones as crew from the Saale, Main and Bremen had to abandon their ships and jumped overboard, as their friends aboard the Kaiser tried to save them.

Finally, those aboard the Kaiser heard the alarm bells of the tugs that had come to save the ship. Seven arrived quickly to save the ship, two at the bow, and five at the stern, and all pulled the liner away from the piers and towards the open water as she burned. Now that the crew finally had a chance to fight the fires in peace, they did without hesitation. The bow, forecastle and Boat Deck were already ablaze. The fire was put out efficiently but seven lifeboats were beyond repair and even worse, two crew members were lost forever. The other three NDL vessels were all horrifically damaged with high losses onboard. All three were repaired and resumed service in the later years. As for the NDL piers, they were nothing but rubble. Even Hapag’s own piers nearby had been pulled down to stop the fire from spreading. In total, 326 people were killed aboard these four piers and during the fire, and that could even have been far worse had the ships be loaded with passengers that day, and not cargo.

The Collision in Cherbourg

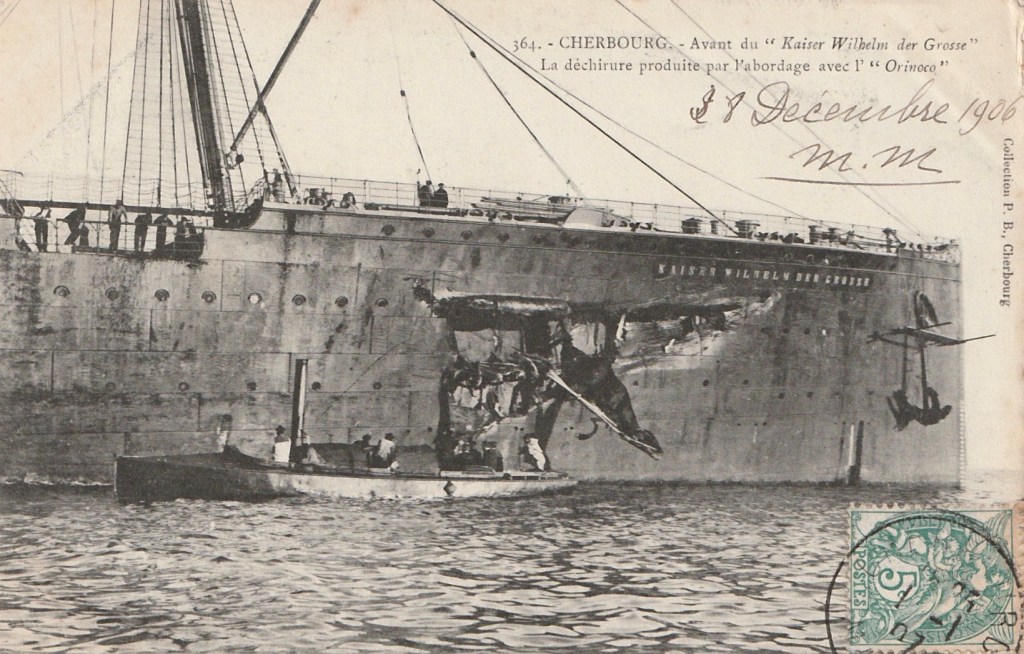

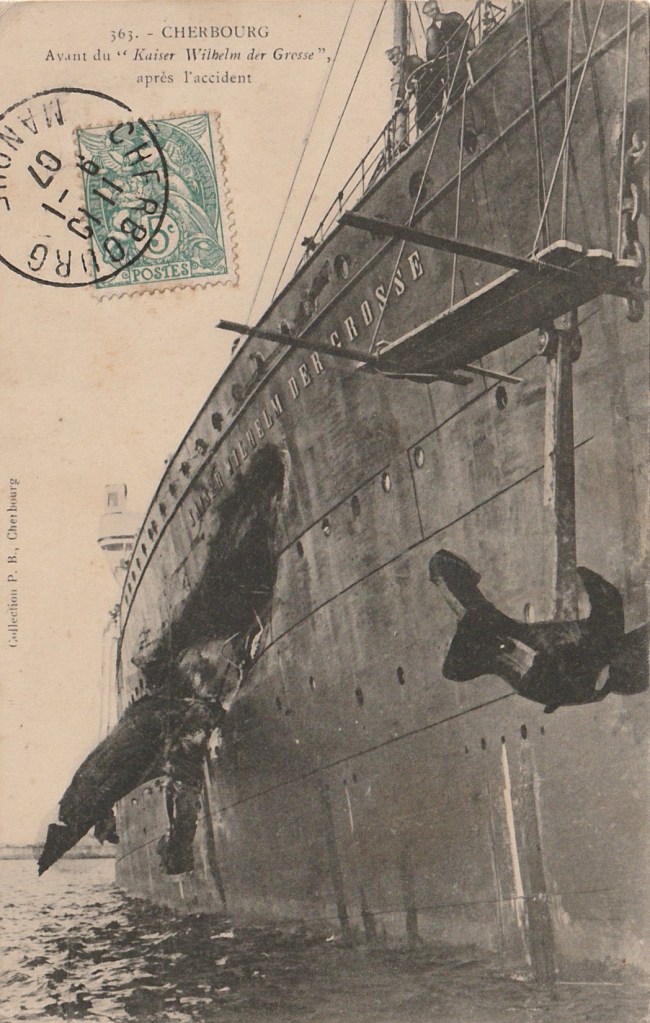

It was the 21st November 1906 at the last stop before New York: Cherbourg France. It was around 18:00 in the evening and the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse received the expected mail and passengers from one of the North German Lloyd tenders. An hour later, she raised anchor and began to leave the harbour from the west to the open sea. She was commanded by Captain O. Cüppers with First Officer F. Iseke and another officer on the starboard bridge wing. The port bridge wing had another officer and two more were inside the bridge at the telegraphs with the helmsman behind them. Finally, in the crows nest were two lookouts also scanning the water ahead.

The night was extremely dark, with some fog, and all eight crewmembers followed the beacons and buoys in the water that would lead them to the harbour exit. Cherbourg was a sea town, almost completely surrounded by a gigantic pier. From the bridge, they noticed the lights of an approaching vessel. This was the Orinoco of 4527 GRT, that was entering Cherbourg with her 64 passengers. There was no immediate danger as both ships drew closer, those on the Kaiser expected the Orinoco to turn towards the east pier head and sail behind them. However that didn’t happen and the Kaisers engines were ordered into full steam ahead. The whistles gave two short blasts, alerting the Orinoco that the Kaiser wanted to pass them on their starboard side, so Orinoco should make for the left. Unfortunately at that exact moment the Orinoco sounded her own signal, drowning out the Kaiser’s that they wanted to pass them on their starboard side. This miscommunication created a collision course as both ships were only 500m away now. Immediately upon this realisation, the engines of the Kaiser were ordered into reverse and the propellors stopped, but the ship was already travelling very fast at 18 knots. Both ships could only see each others lights and this aided their misjudgements, the collision was eminent.

(Author’s Collection)

The Orinoco slammed into the starboard bow of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, easily ripping up the plates and remained stuck fast. The damage stretched three decks from the second bulkhead to the foremast, tearing into two steerage quarters where the bunks were. One cargo room below was also exposed. The Kaiser had been turning to port during the collision, and this further allowed the Orinoco to dig in. Those in the lower decks received such a horrible rude awakening, as the sharp prow of the Orinoco burst through the side of the Kaiser. This was the complete opposite for First Class passengers on the upper decks, as they hardly felt anything. Immediately during this incident: Captain Cüppers shouted two orders:

Both engines – stop!

Send the ship’s doctor below decks immediately!

Captain Cüppers also sent Officer Löding to help the Steerage passengers in any way possible and Officer Hasselmann to the upper passengers to keep them calm and assured there was no danger. He then ordered the ship to start, and and to reverse slowly away from the Orinoco. All crew immediately were put to work, some using saws and axes to free the badly-injured passengers and to pull the ship away from the Orinoco. It took 10 minutes for the Orinoco to be pried off the Kaiser and she pulled out even more plates during her exit. Fortunately all damage was above the waterline, so both ships were safe from sinking.

Now it was time to go, and the Kaiser sailed back into Cherbourg harbour the next day and anchored off the pier. Orinoco was tied to a buoy as her bow anchors were inoperable after the collision. This was not the biggest issue, as several crew members panicked during the collision and hastily launched two lifeboats and hopped in. One of the boats was overloaded due to the panic and overturned, tossing people into the water. Three crew members sadly drowned despite immediate rescue being given. Casualties on the Kaiser were even greater, not a single crew member had been injured but four passengers were killed on the spot by the prow of Orinoco, and nine more were critically injured. Those lost were of the names: Michael Muhlbeier and Samuel Grolscant of Worms, Michael Zimbelmann of Forbach, and Anna Koucelik of Cecelowiz, Bohemia. Rockets and flares were used to signal distress to the mainland, and Captain Cüppers sent an officer in a lifeboat with the dead and injured back to the tender, to be brought ashore to the hospital as quickly as possible. More tragedy still struck, as one of the severely injured – a young girl named Stevier, passed away before reaching land.

The Kaiser’s damages were inspected and it was declared she was unfit to sail to New York. Estimates for the repair bill were put at $200’000. Orinoco also similarly cancelled her voyage. Both ships were so severely damaged: they had to steam back to their homelands for immediate emergency repair. They left, without their passengers, luggage or mail and these were taken back ashore by tender. In the ensuing court case for the disaster: the entire blame was placed fully on the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse as the ship should have heeded the Orinoco’s message that was she was turning to starboard.

The 1913 rebuild

On the 27th September 1913, the NDL announced that they were planning to withdraw the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse from express service with its sisters, and instead put it on migrant service. This was a rather sad time as the vessel that had pushed the company into a new era was delegated to be not as important as it once was, since competition had risen so rapidly over the last 15 years. From this point forward to the end of her passenger-carrying career, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was to sail as a third-class only ship.

Further Career

- Several of the esteemed guests the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse would carry during her career would include: Kaiser Wilhelm II and sixty guests on a special cruise in 1898, John Jacob Astor IV would take many trips on all five German four-stacker no less this one, Alice Roosevelt – daughter of President Roosevelt climbed the ropes of the Kaiser to many cheers in January 1906, Orville and Katherine Wright would cross in January 1909, Composer Sergei Rachmaninoff in February 1910

- One curious mystery aboard the Kaiser was the theft of three gold bars valued at £4000 each from the ship’s treasure vault on April 9th 1901 after docking in Cherbourg under the command of Captain Engelbart. Immense searching of all baggage occurred, detectives travelled with the 150 passengers who left for Paris and a reward of 10’000 marks was offered by the Lloyd for their discovery. They would be found 5 days later, stashed aboard the ship by a steward named Theodore Mayers. The suspect was believed to be a crew member.

- In October 1907 during an eastbound crossing 1300 miles away from New York, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was struck by a colossal wave from behind that lifted the stern up high, and completely tore off the rudder. Under expert command of Captain Pollack, the ship was steered just using her twin screws at a speed of 18 knots back to Britain. Polack refused assistance from 21 different vessels and safely steered the massive ship to shore. After hearing of this incredible feat of navigation, Kaiser Wilhelm II himself decorated Polack. By amazing coincidence in April 0f 1901, the Kaiser’s rival: the Deutschland had suffered the exact same incident when her rudder was also torn off and her captain Albers steered his own ship for hundreds of miles without assistance back to Cuxhaven using just the propellors. Sadly in this case, Captain Albers passed away from a heart attack as soon as landing.

- On March 19th 1914, a three-masted sailing ship suddenly appeared in front of the Kaiser at night and was immediately rammed and cut down. Despite search efforts, no survivors where ever found and even the identity and name of the ship was never discovered.

- After 17 proud years of service, the world’s first superliner would undertake her last role in 1914.

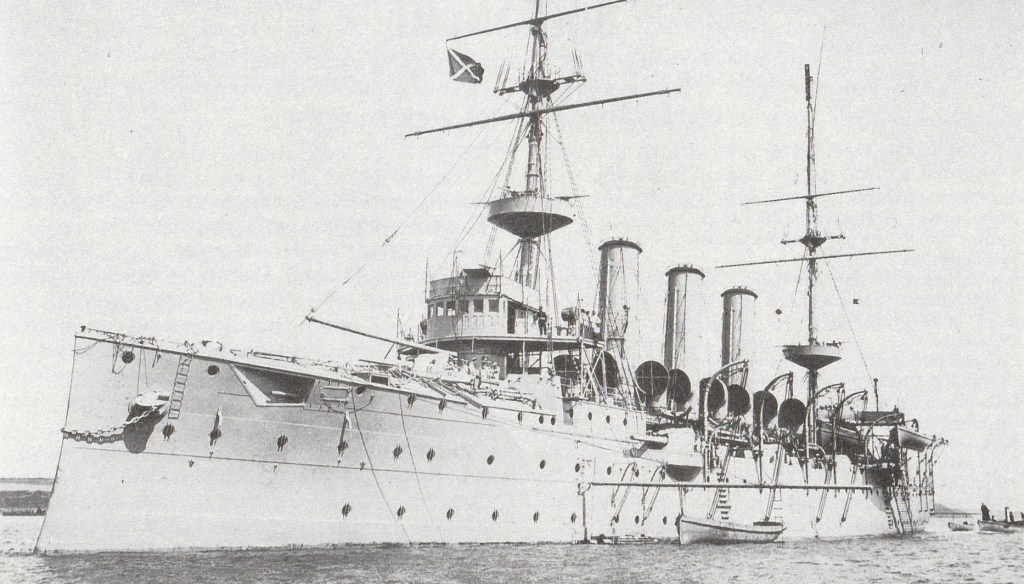

Hilfskreuzer Kaiser Wilhem der Grosse

On August 1st 1914, Germany declared war on Russia following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austrian Hungarian Empire. All available resources had to be used to aid the war effort and that absolutely applied to the country’s merchant shipping fleet. In fact, certain ships such as Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse had been intended to assist during war as she had been built with reinforced decks and special mounts to carry arms. As soon as war had been declared, Germany’s light cruisers began raiding and sinking Allied commerce to aid the war effort and stop the spread of supplies. Despite their work, the Royal Navy undoubtedly outsized the Kaiserliche Marine with a ratio of 117:47 in just cruisers. In 1914 merchant ships like Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse despite their slower speed, had the endurance and size to stay on the seas for weeks and live off their captees.

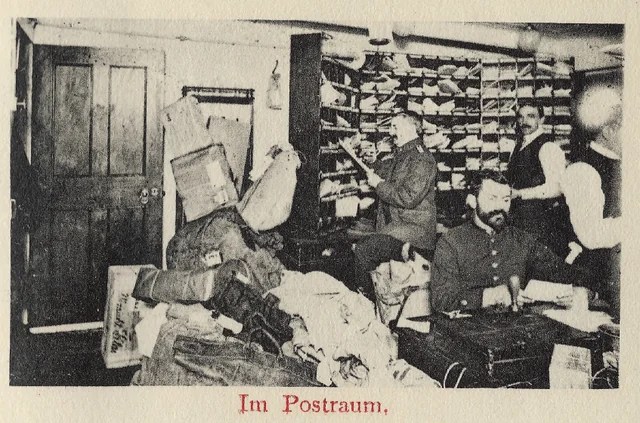

Immediately, in late July 1914 the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was taken in by the Lloyd, and refitted to become an auxiliary cruiser. Her sisters were all abroad in New York whilst she had been at home. The ship received six 10.5cm guns, and was repainted grey, with black funnels. Two guns were placed each on the bow, on the wellend deck and the stern. Just three days after war began on the 4th August, the ship departed Germany under the command of Captain S. Reymann to raid prizes in the North Atlantic. She found one soon, fifty nautical miles north-west of Iceland: The 227 GRT trawler Tubal Cain, built in 1905 for Rushworth & Atkinson of Grimsby. By August 15th, coal was running low and she fortunately located another prize: the 6’762-ton Galican of the Union Castle Line. The vessel was captured by the sly deception of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse:

The Gallican first asked nearby vessels if the coast was clear. The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse broadcasted this message:

“We will meet you, there is greater safety in numbers.”

At 14:25pm, the two vessels met and the Galican received a far more ominous greeting than she had expected:

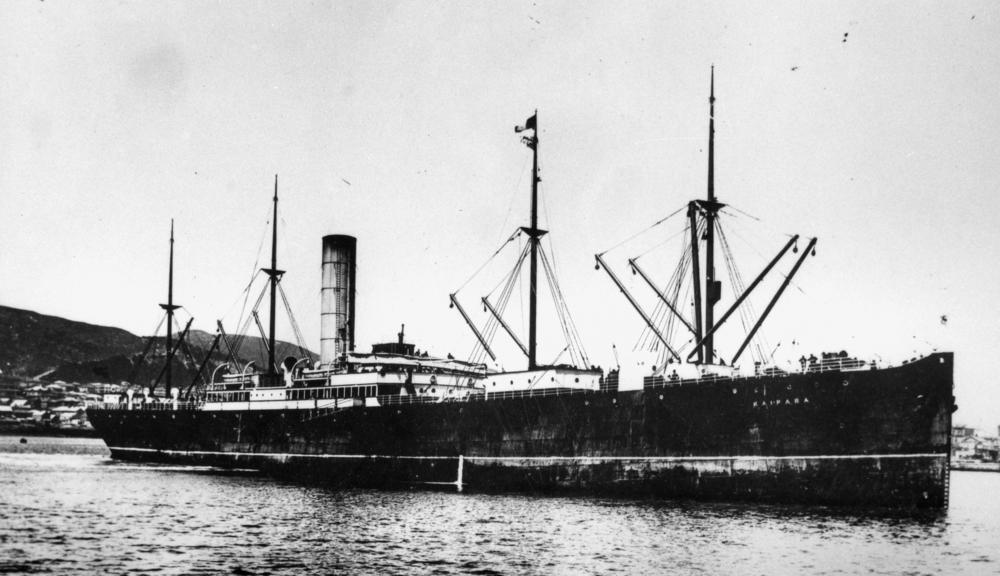

“Do not use your wireless or I will sink you.”

The raiding party went aboard the Galican to assess their prize, but discovered a passenger of 250, mostly women and children. The Galican was let go 05:00 the next day. The loss of one prize was quickly corrected by the capture of another just two hours later: the 7392 GRT freighter: Kaipara, belonging New Zealand Shipping Co. Ltd. Her cargo of meat was very much appreciated by the Kaiser, and after passengers had been loaded aboard, the Kaipara went down after her seacocks had been opened and she had been gunned by apparently a ridiculous fifty-three 10.5cm shells. More bounty was to come this same day as they sighted the massive 15’044 GRT Arlanza, of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. But once again, this ship was carrying 335 women and almost 100 children so she was released.

On the 16th August, the Kaiser’s second prize was spotted: the freighter Nyanga of 3066 GRT, owned by Elder Line Ltd. The ships cargo and was taken aboard the Kaiser as was all on board, and the ship was sunk by opening the sea cocks again and detonating explosive charges. Unfortunately, the Kaiser was running low on coal by this point, and arrangements were made to meet up with two colliers using the Etappe system: a supply network for German ships during the war in neutral countries. The colliers were Arucas and Duala, and the three met up in Rio de Oro on the 21st August, breaking neutrality rules. They were joined by the 4497 GRT Magdeburg of the Deutsch-Australische Dampfschiffs-Gesellschaft, and the 7548 GRT HAPAG vessel, Bethania. For five days, coal and supplies were taken aboard the Kaiser and they even fooled Spanish officials into believing the Kaiser was an ordinary liner having her engines fixed by the colliers. It was on this day that a new vessel would join them, the complete opposite kind to give assistance.

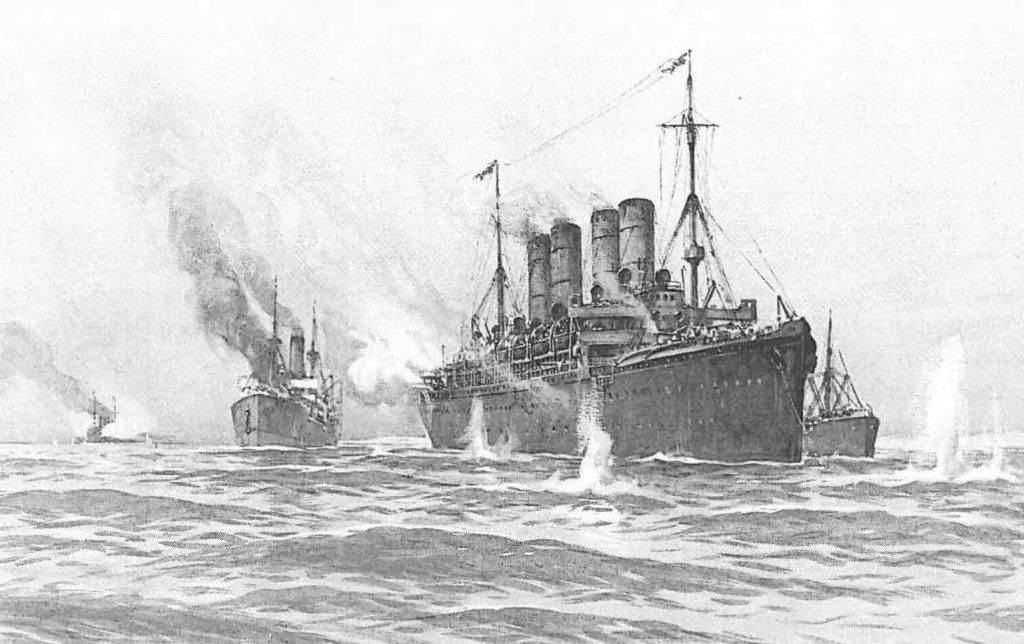

Sinking

The Kaiser was still taking in coal, when the lookouts on the foremast spotted a three-funnelled vessel approaching, bearing the White Ensign. This was the 5560-ton British cruiser: HMS Highflyer, searching for the Kaiser. There was major panic aboard the four vessels including the Kaiser, Reymann ordered guns cleared for action and the colliers sped away. Highflyer was bearing down on them with 11 six-inch guns compared to the Kaiser’s four 10.5cm arms. The only real option was to flee and the Kaiser was the faster vessel compared to Highflyer’s 20.1 knots and had a good chance, but they had no steam. Highflyer’s captain invited them to surrender, but they were refused and both ships swung out to battle.

The battle lasted an hour and a half, Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse landed several hits, but every shot from Highflyer’s 6-inch guns was unbearably deadly and the ex-luxury liner was torn up and set ablaze. At 16:20pm she rolled over to starboard and went down in shallow water off Durnard Point at exactly (23°34’N16°02’W). As for what caused the ship to sink, that has never been definitively confirmed. The British claimed they sank the Kaiser, whilst the Germans claimed they scuttled their own ship to avoid capture. That didn’t matter however, as the raider Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was taken off the ocean surface forever.

In terms of casualties, Highflyer lost one man and estimates for those lost aboard the Kaiser vary massively: some estimates being not a single man was lost, whilst other say roughly 100 men were lost. 400 men had been rescued by Bethania which was still in the vicinity, whilst Reymann, nine officers and 71 men boarded the lifeboats and sailed ashore. They then walked to the nearest Spanish post and surrendered. The crews of the two prizes of the Kaiser: Kaipara and Nyanga were successfully evacuated aboard the colliers Arucas and Duala before the battle began.

Bibliography

- (1913) To rebuild big Kaiser Wilhelm, New York Times. September 28th.

- (1954) Mielke, Otto SOS Schicksale Deutscher Schiffe Nr. 34 “Vom Luxusdampfer zum Hilfskreuzer”, Arthur Moeewig Verlag, Munich

- Kludas, Arnold (1987) Die Geschichte der Deutschen Passagierschiffart Band II: Expansionen auf allen Meeren 1890 bis 1900. Ernst Kabel Verlages, Hamburg.

- Kludas, Arnold (2000) Record Breakers of the North Atlantic, Blue Riband Liners 1838 – 1952 Chatham Publishing, London.

- Shaum Jr, John H. & Flayhart III, William H. , (1981) Majesty at Sea, The Four Stackers, W.W. Norton and Company, New York London

- Totzke, Thorsten, LostLiners.de https://lostliners.de/schiffe/k/kwdg/geschichte/index.htm (Accessed August 2025)

- CAPTAIN OF THE KAISER BLAMED FOR COLLISION; New York Times, November 23rd

- Earl of Cruise https://earlofcruise.blogspot.com/2016/06/german-greyhounds-ii_80.html (Accessed August 2025)

- 1906 : https://www.nytimes.com/1906/11/23/archives/captain-of-the-kaiser-blamed-for-collision-commander-of-the-orinoco.html?searchResultPosition=40

- IN FAVOR OF THE ORINOCO.; New York Times, November 24th 1906 : https://www.nytimes.com/1906/11/24/archives/in-favor-of-the-orinoco-preliminary-inquiry-tends-to-place-the.html?searchResultPosition=41

- GERMAN EMPERORS SEA TRIP: New York Times, March 27th 1898 : https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1898/03/27/102108923.html?pageNumber=7

- GOLD STOLEN ON LINER : New York Times, April 10th 1901 : https://www.nytimes.com/1901/04/10/archives/gold-stolen-on-liner-three-bars-worth-u12000-missing-from-the.html?searchResultPosition=73

- GOLD BARS HAVE BEEN FOUND: New York Times 14th April 1901 https://www.nytimes.com/1901/04/11/archives/the-theft-of-gold-bars-north-german-lloyd-steamship-company-offers.html?searchResultPosition=75

- MISS ROOSEVELT CLIMBS ROPE LADDER TO LINER: January 31st 1906 https://www.nytimes.com/1906/01/31/archives/miss-roosevelt-climbs-rope-ladder-to-liner-mr-longworths-efforts-to.html?searchResultPosition=212